I want your feedback to make the book better for you and other readers. If you find typos, errors, or places where the text may be improved, please let me know. The best ways to provide feedback are by GitHub or hypothes.is annotations.

Opening an issue or submitting a pull request on GitHub: https://github.com/isaactpetersen/Principles-Psychological-Assessment

Adding an annotation using hypothes.is.

To add an annotation, select some text and then click the

symbol on the pop-up menu.

To see the annotations of others, click the

symbol in the upper right-hand corner of the page.

Chapter 7 Structural Equation Modeling

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

— George Box (1979, p. 202)

7.1 Overview of SEM

Structural equation modeling is an advanced modeling approach that allows estimating latent variables to account for measurement error and to get purer estimates of constructs.

7.2 Getting Started

7.2.1 Load Libraries

Code

library("petersenlab") #to install: install.packages("remotes"); remotes::install_github("DevPsyLab/petersenlab")

library("lavaan")

library("semTools")

library("semPlot")

library("simsem")

library("snow")

library("mice")

library("quantreg")

library("nonnest2")

library("MOTE")

library("tidyverse")

library("here")

library("tinytex")7.2.2 Prepare Data

7.2.2.1 Simulate Data

For reproducibility, I set the seed below. Using the same seed will yield the same answer every time. There is nothing special about this particular seed.

The petersenlab package (Petersen, 2025) includes a complement() function (archived at https://perma.cc/S26F-QSW3) that simulates data with a specified correlation in relation to an existing variable.

PoliticalDemocracy refers to the Industrialization and Political Democracy data set from the lavaan package (Rosseel et al., 2022), and it contains measures of political democracy and industrialization in developing countries.

Code

sampleSize <- 300

set.seed(52242)

v1 <- complement(PoliticalDemocracy$y1, .4)

v2 <- complement(PoliticalDemocracy$y1, .4)

v3 <- complement(PoliticalDemocracy$y1, .4)

v4 <- complement(PoliticalDemocracy$y1, .4)

PoliticalDemocracy$v1 <- v1

PoliticalDemocracy$v2 <- v2

PoliticalDemocracy$v3 <- v3

PoliticalDemocracy$v4 <- v4

measure1 <- rnorm(n = sampleSize, mean = 50, sd = 10)

measure2 <- measure1 + rnorm(n = sampleSize, mean = 0, sd = 15)

measure3 <- measure1 + measure2 + rnorm(n = sampleSize, mean = 0, sd = 15)7.3 Types of Models

Structural equation modeling (SEM) involves the use of models. A model is a simplification of reality.

7.3.1 Path Analysis Model

To understand structural equation modeling (SEM), it is helpful to first understand path analysis. Path analysis is similar to multiple regression. Path analysis allows examining the association between multiple predictor variables (or independent variables) in relation to an outcome variable (or dependent variable). Unlike multiple regression, however, path analysis also allows inclusion of multiple dependent variables in the same model. Unlike SEM, path analysis uses only manifest (observed) variables, not latent variables (described next). SEM is path analysis, but with latent (unobserved) variables. That is, a SEM model is a model that includes latent variables in addition to observed variables, where one attempts to model (i.e., explain) the structure of associations between variance using a series of equations (hence structural equation modeling).

7.3.2 Components of a Structural Equation Model

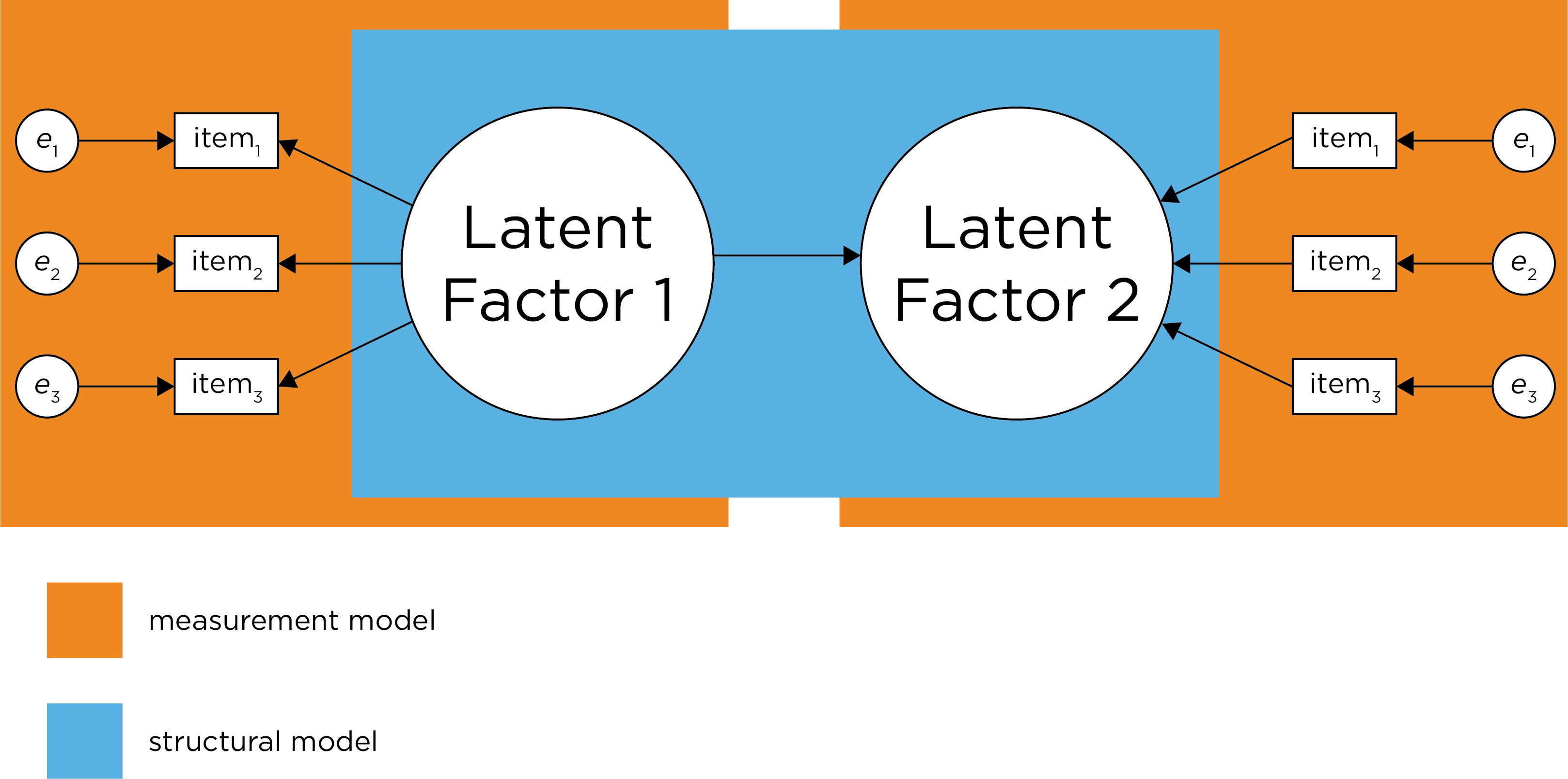

7.3.2.1 Measurement Model

The measurement model is a crucial sub-component of any SEM model. A SEM model consists of two components: a measurement model and a structural model. The measurement model is a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model that identifies how many latent factors are estimated, and which items load onto which latent factor. The measurement model can also specify correlated residuals. Basically, the measurement model specifies your best understanding of the structure of the latent construct(s) given how they were assessed. Before fitting the structural component of a SEM, it is important to have a well-fitting measurement model for each construct in the model. In Section 7.3.2.1, I present an example of a measurement model.

7.3.2.2 Structural Model

The structural component of a SEM model includes the regression paths that specify the hypothesized causal relations among the latent variables. The disturbance (error term) for endogenous latent factors (i.e., latent factors that are predicted by other predictors) in the structural model is called zeta (\(\zeta\)).

7.3.3 Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is a subset of SEM. CFA includes the measurement model but not the structural component of the model. In Section 7.10, I present an example of a CFA model. I discuss CFA models in greater depth in Chapter 14.

7.3.4 Structural Equation Model

SEM is CFA, but it adds regression paths that specify hypothesized causal relations between the latent variables, which is called the structural component of the model. The structural model includes the hypothesized causal relations between latent variables. A SEM model includes both the measurement model and the structural model (see Figure 7.1, Civelek, 2018). SEM fits a model to observed data, or the variance-covariance matrix, and evaluates the degree of model misfit. That is, fit indices evaluate how likely it is that a given model gave rise to the observed data. In Section 7.11, I present an example of a SEM model.

Figure 7.1: Demarcation Between Measurement Model and Structural Model. Disturbance term is zeta. (Figure adapted from Civelek (2018), Figure 1, p. 7. Civelek, M. E. (2018). Essentials of structural equation modeling. Zea E-Books. https://doi.org/10.13014/K2SJ1HR5)

SEM is flexible in allowing you to specify measurement error and correlated errors. Thus, you do not need the same assumptions as in classical test theory, which assumes that errors are random and uncorrelated. But the flexibility of SEM also poses challenges because you must explicitly decide what to include—and not include—in your model. This flexibility can be both a blessing and a curse. If the model fit is unacceptable, you can try fitting a different model to see which fits better. Nevertheless, it is important to use theory as a guide when specifying and comparing competing models, and not just rely solely on model fit comparison. For example, the model you fit should depend on how you conceptualize each construct: as reflective or formative.

7.4 Estimating Latent Factors

7.4.1 Model Identification

7.4.1.1 Types of Model Identification

There are important practical issues to consider with both reflective and formative models. An important practical issue is model identification—adding enough constraints so that there is only one, best answer. The model is identified when each of the estimated parameters has a unique solution. For ensuring the model is identifiable, see the criteria for identification of the measurement and structural model here (archived at https://perma.cc/5C9E-LBWM).

Degrees of freedom in a SEM model is the number of known values minus the number of estimated parameters. The number of known values in a SEM model is the number of variances and covariances in the variance-covariance matrix of the manifest (observed) variables in addition to the number of means (i.e., the number of manifest variables), which can be calculated as: \(\frac{m(m + 1)}{2} + m\), where \(m = \text{the number of manifest variables}\). You can never estimate more parameters than the number of known values. A model with zero degrees of freedom is considered “saturated”—it will have perfect fit because the model estimates as many parameters as there are known values. All things equal (i.e., in terms of model fit with the same number of manifest variables), a model with more degrees of freedom is preferred for its parsimony, because fewer parameters are estimated.

Based on the number of known values compared to the number of estimated parameters, a model can be considered either just identified, under-identified, or over-identified. A just identified model is a model in which the number of known values is equal to the number of parameters to be estimated (degrees of freedom = 0). An under-identified model is a model in which the number of known values is less than the number of parameters to be estimated (degrees of freedom < 0). An over-identified model is a model in which the number of known values is greater than the number of parameters to be estimated (degrees of freedom > 0).

As an example, there are 14 known values for a model with 4 manifest variables (\(\frac{4(4 + 1)}{2} + 4 = 14\)): 4 variances, 6 covariances, and 4 means.

Here is the variance-covariance matrix:

Code

y1 y2 y3 y4

y1 6.387379 NA NA NA

y2 6.060140 16.424848 NA NA

y3 5.613202 6.329419 11.066049 NA

y4 5.393572 9.910746 7.151898 11.22069Here are the variances:

y1 y2 y3 y4

6.387379 16.424848 11.066049 11.220691 Here are the covariances:

Code

[1] 6.060140 5.613202 5.393572 6.329419 9.910746 7.151898Here are the means:

Code

y1 y2 y3 y4

5.347059 4.284975 6.367156 4.356618 7.4.1.2 Approaches to Model Identification

The three most widely used approaches to identifying latent factors are:

7.4.1.2.1 Marker Variable Method

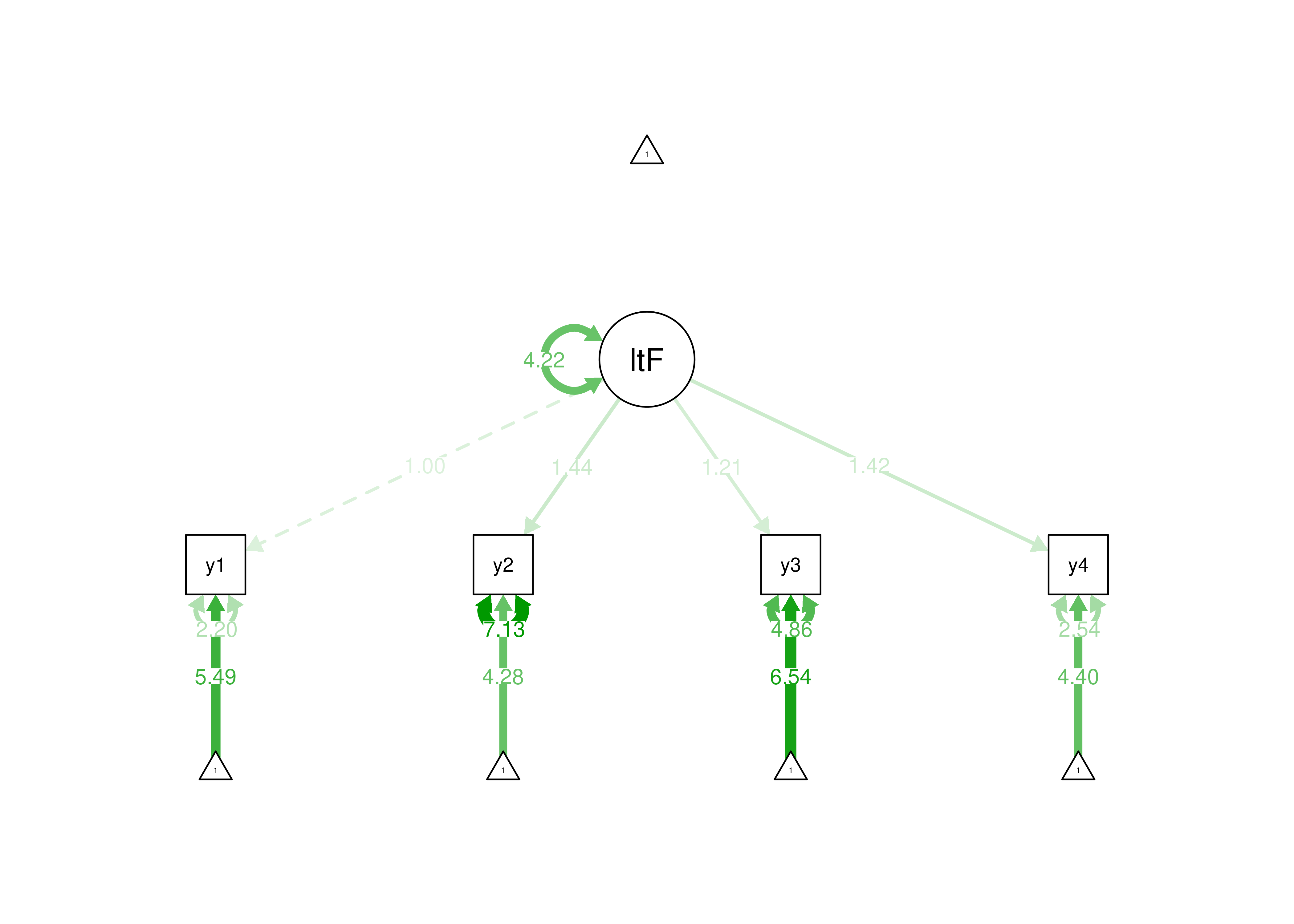

In the marker variable method, one of the indicators (i.e., manifest variables) is set to have a loading of 1. Here are examples of using the marker variable method for identification of a latent variable:

Code

markerVariable_syntax <- '

#Factor loadings

latentFactor =~ y1 + y2 + y3 + y4

'

markerVariable_fullSyntax <- '

#Factor loadings

latentFactor =~ 1*y1 + y2 + y3 + y4

#Latent variance

latentFactor ~~ latentFactor

#Estimate residual variances of manifest variables

y1 ~~ y1

y2 ~~ y2

y3 ~~ y3

y4 ~~ y4

#Estimate intercepts of manifest variables

y1 ~ 1

y2 ~ 1

y3 ~ 1

y4 ~ 1

'

markerVariableModelFit <- sem(

markerVariable_syntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR")

markerVariableModelFit_full <- lavaan(

markerVariable_fullSyntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR")

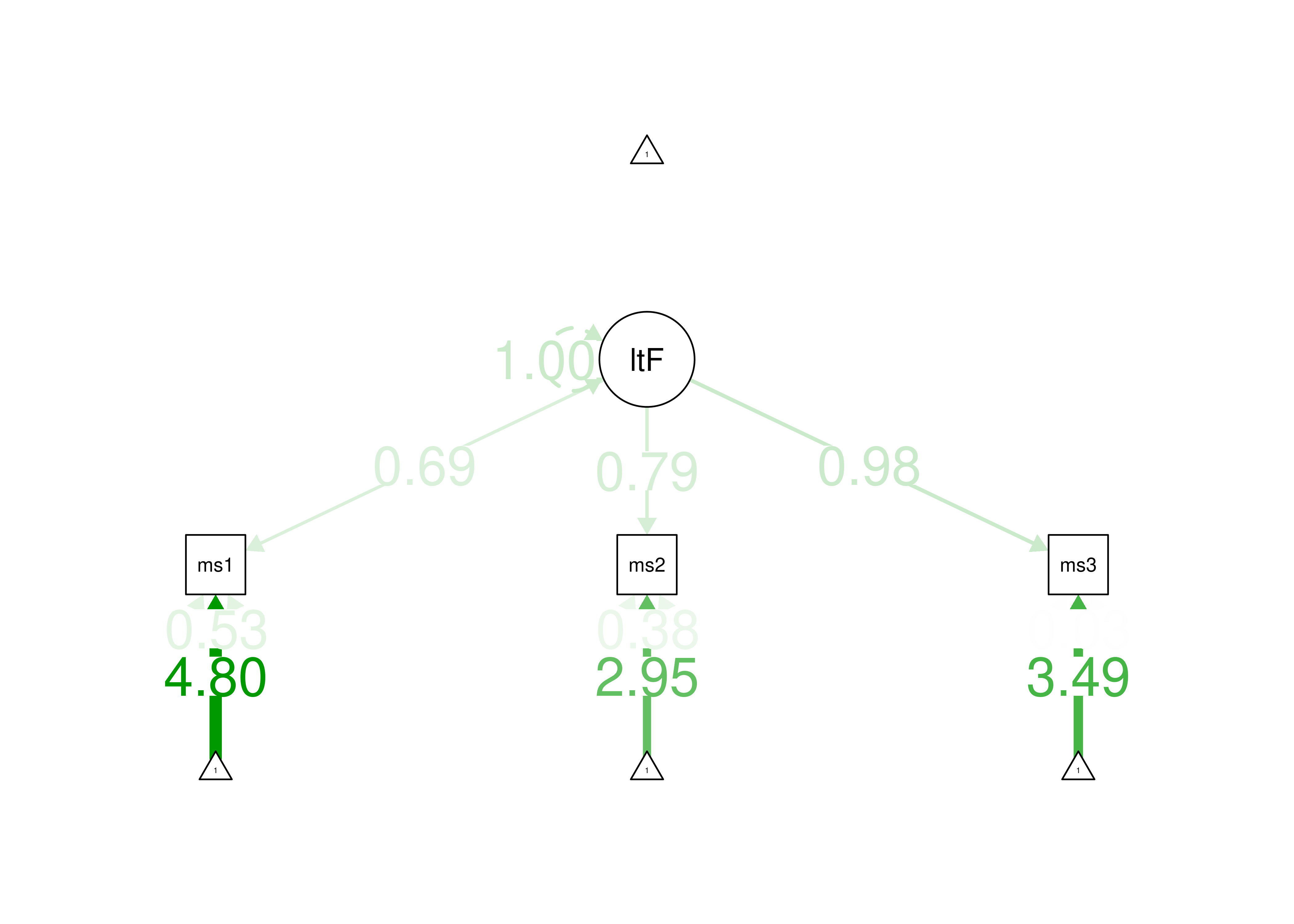

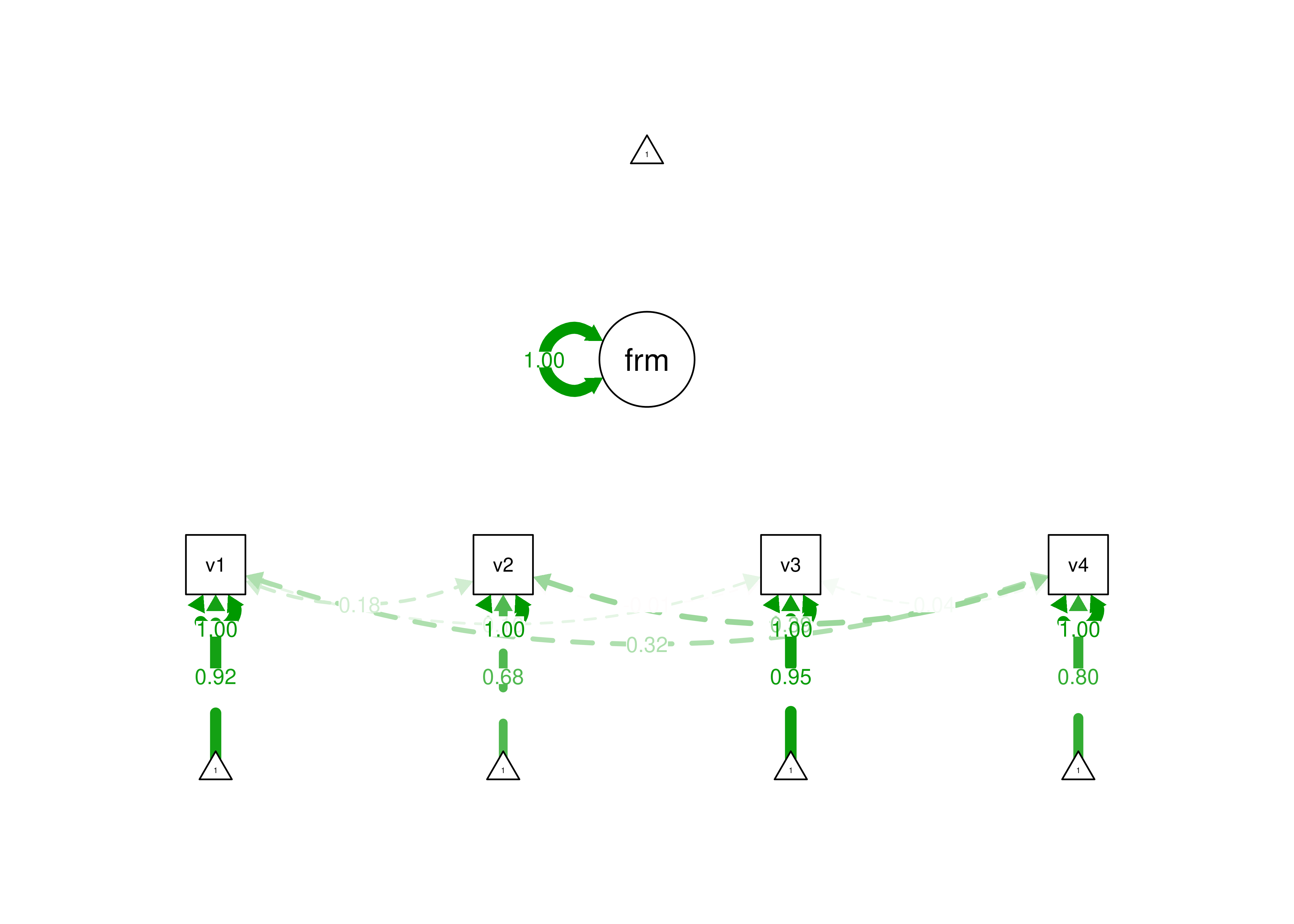

Figure 7.2: Identifying a Latent Variable Using the Marker Variable Approach.

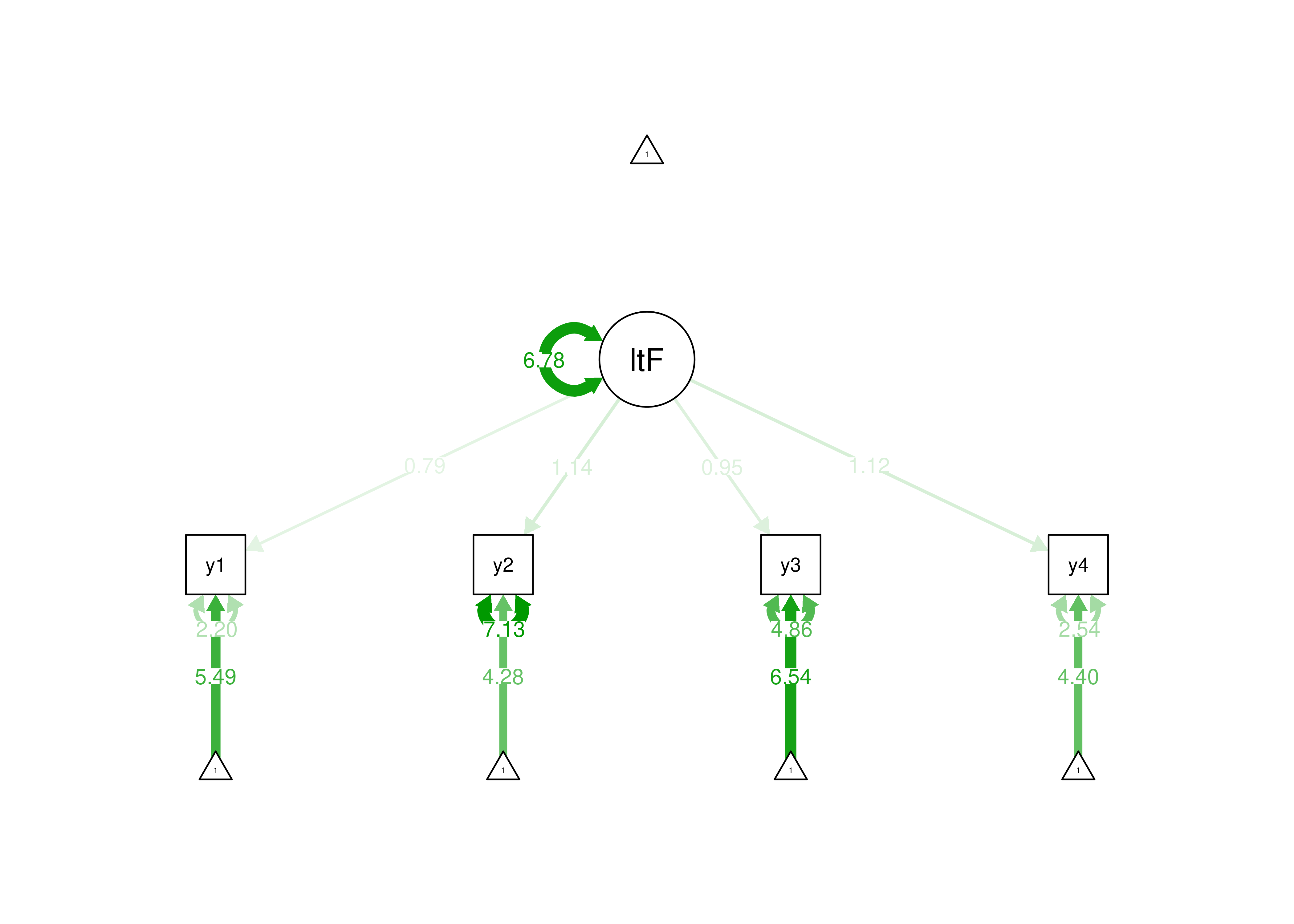

7.4.1.2.2 Effects Coding Method

In the effects coding method, the average of the factor loadings is set to be 1. The effects coding method is useful if you are interested in the means or variances of the latent factor, because the metric of the latent factor is on the metric of the indicators. Here are examples of using the effects coding method for identification of a latent variable:

Code

effectsCoding_abbreviatedSyntax <- '

#Factor loadings

latentFactor =~ y1 + y2 + y3 + y4

'

effectsCoding_syntax <- '

#Factor loadings

latentFactor =~ NA*y1 + label1*y1 + label2*y2 + label3*y3 + label4*y4

#Constrain factor loadings

label1 == 4 - label2 - label3 - label4 # 4 = number of indicators

'

effectsCoding_fullSyntax <- '

#Factor loadings

latentFactor =~ label1*y1 + label2*y2 + label3*y3 + label4*y4

#Constrain factor loadings

label1 == 4 - label2 - label3 - label4 # 4 = number of indicators

#Latent variance

latentFactor ~~ latentFactor

#Estimate residual variances of manifest variables

y1 ~~ y1

y2 ~~ y2

y3 ~~ y3

y4 ~~ y4

#Estimate intercepts of manifest variables

y1 ~ 1

y2 ~ 1

y3 ~ 1

y4 ~ 1

'

effectsCodingModelFit_abbreviated <- sem(

effectsCoding_abbreviatedSyntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

effect.coding = "loadings",

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR")

effectsCodingModelFit <- sem(

effectsCoding_syntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR")

effectsCodingModelFit_full <- lavaan(

effectsCoding_fullSyntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR")

Figure 7.3: Identifying a Latent Variable Using the Effects Coding Approach.

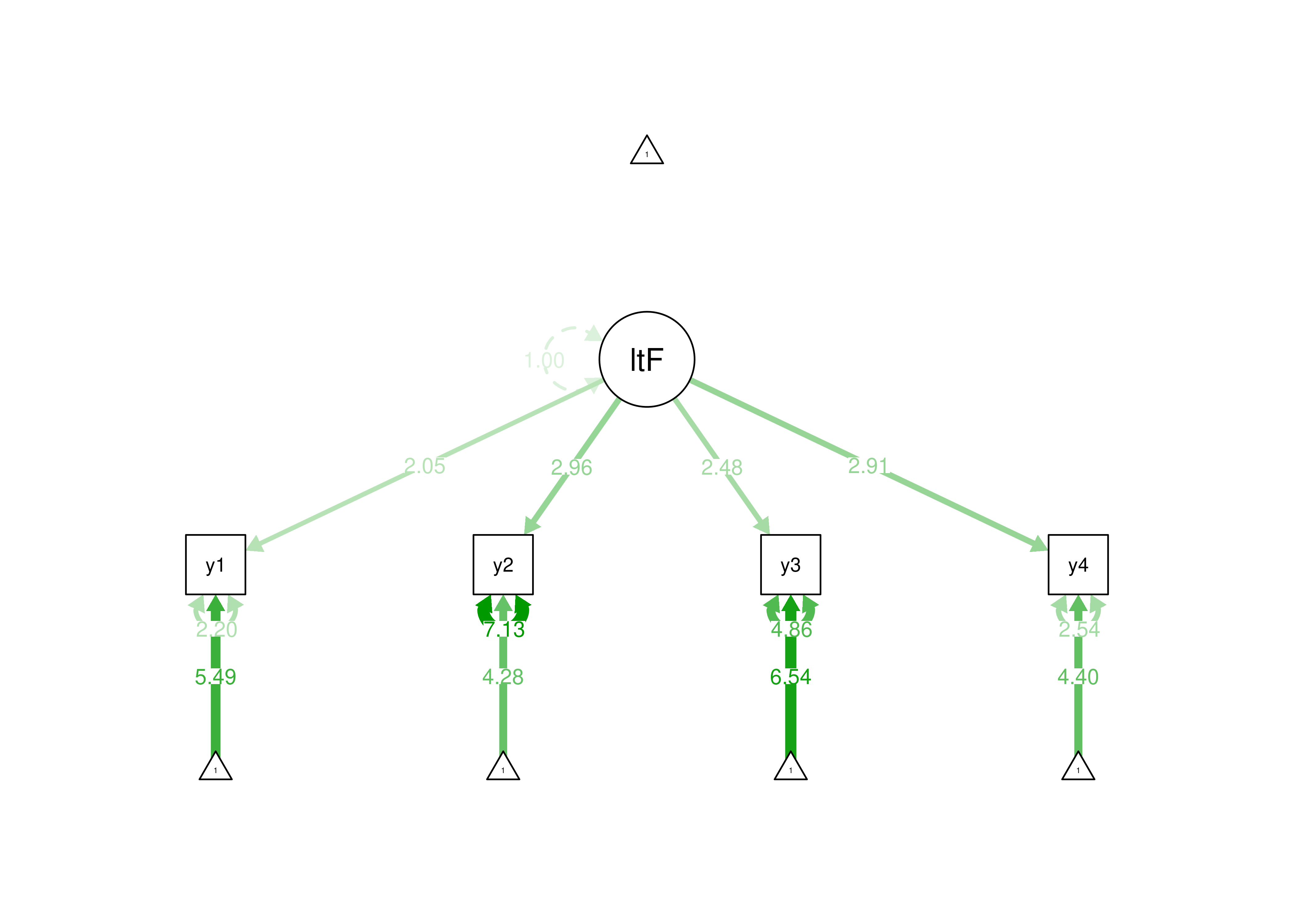

7.4.1.2.3 Standardized Latent Factor Method

In the standardized latent factor method, the latent factor is set to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. The standardized latent factor method is a useful approach if you are not interested in the means or variances of the latent factors and want to freely estimate the factor loadings. Here are examples of using the standardized latent factor method for identification of a latent variable:

Code

standardizedLatent_abbreviatedsyntax <- '

#Factor loadings

latentFactor =~ y1 + y2 + y3 + y4

'

standardizedLatent_syntax <- '

#Factor loadings

latentFactor =~ NA*y1 + y2 + y3 + y4

#Latent mean

latentFactor ~ 0

#Latent variance

latentFactor ~~ 1*latentFactor

'

standardizedLatent_fullSyntax <- '

#Factor loadings

latentFactor =~ NA*y1 + y2 + y3 + y4

#Latent mean

latentFactor ~ 0

#Latent variance

latentFactor ~~ 1*latentFactor

#Estimate residual variances of manifest variables

y1 ~~ y1

y2 ~~ y2

y3 ~~ y3

y4 ~~ y4

#Estimate intercepts of manifest variables

y1 ~ 1

y2 ~ 1

y3 ~ 1

y4 ~ 1

'

standardizedLatentFit_abbreviated <- sem(

standardizedLatent_abbreviatedsyntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

std.lv = TRUE,

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR")

standardizedLatentFit <- sem(

standardizedLatent_syntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR")

standardizedLatentFit_full <- lavaan(

standardizedLatent_fullSyntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR")

Figure 7.4: Identifying a Latent Variable Using the Standardized Latent Factor Approach.

7.4.2 Types of Latent Factors

7.4.2.1 Reflective Latent Factors

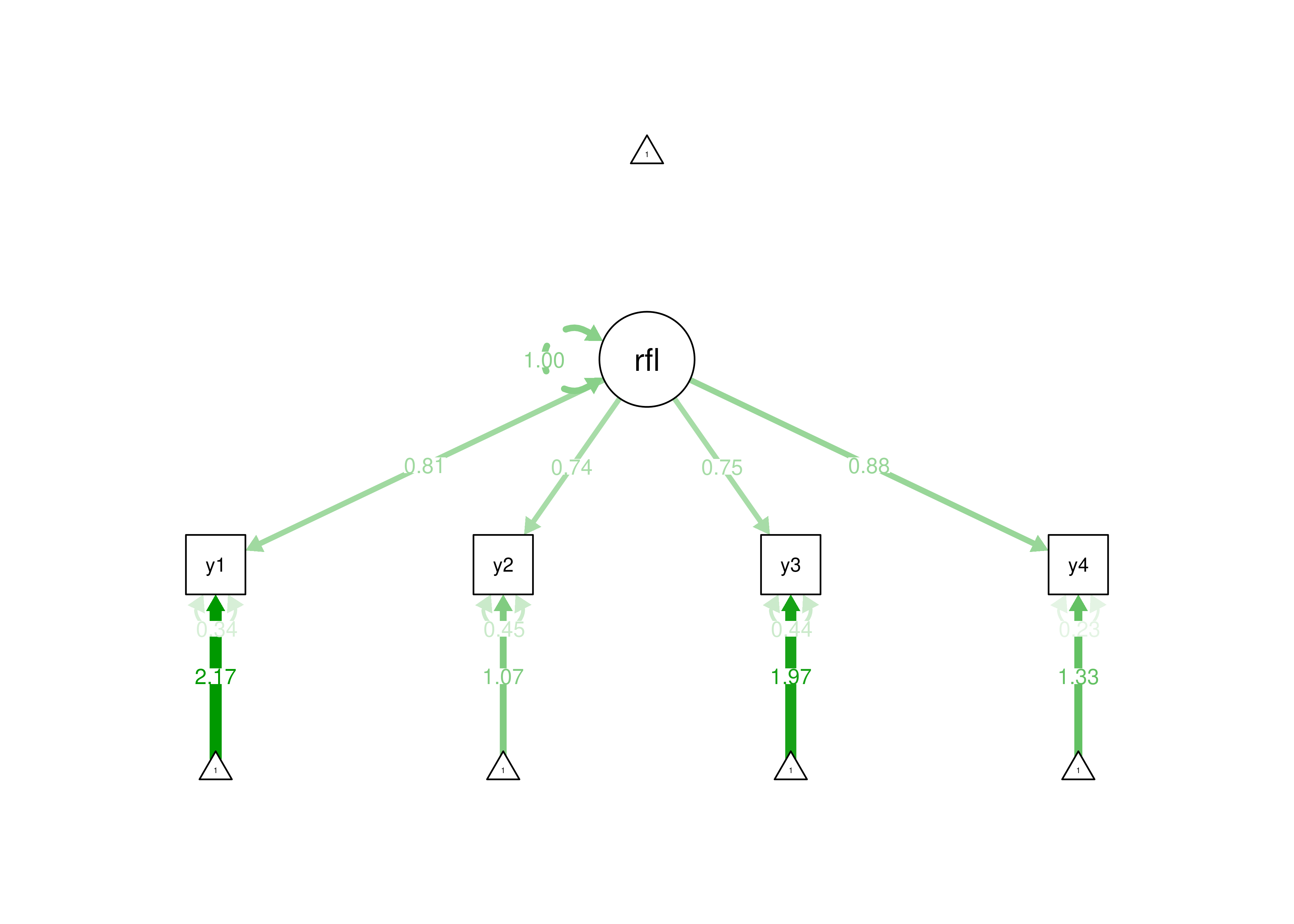

For a reflective model with 4 indicators, we would need to estimate 12 parameters: a factor loading, error term, and intercept for each of the 4 indicators. Here are the parameters estimated:

Code

reflectiveModel_syntax <- '

#Reflective model factor loadings

reflective =~ y1 + y2 + y3 + y4

'

reflectiveModelFit <- sem(

reflectiveModel_syntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR",

std.lv = TRUE)

reflectiveModelParameters <- parameterEstimates(

reflectiveModelFit)[!is.na(parameterEstimates(reflectiveModelFit)$z),]

row.names(reflectiveModelParameters) <- NULL

reflectiveModelParametersHere are the degrees of freedom:

df

2 Here is a model diagram:

Figure 7.5: Example of a Reflective Model.

Thus, for a reflective model, we only have to estimate a small number of parameters to specify what is happening in our model, so the model is parsimonious. With 4 indicators, the number of known values (14) is greater than the number of parameters (12). We have 2 degrees of freedom (\(14 - 12 = 2\)). Because the degrees of freedom is greater than 0, it is easy to identify the model—the model is over-identified. A reflective model with 3 indicators would have 9 known values (\(\frac{3(3 + 1)}{2} + 3 = 9\)), 9 parameters (3 factor loadings, 3 error terms, 3 intercepts), and 0 degrees of freedom, and it would be identifiable because it would be just-identified.

7.4.2.2 Formative Latent Factors

However, for a formative model, we must specify more parameters: a factor loading, intercept, and variance for each of the 4 indicators, all 6 permissive correlations, and 1 error term for the latent variable, for a total of 19 parameters. Here are the parameters estimated:

Code

formativeModel_syntax <- '

#Formative model factor loadings

formative <~ v1 + v2 + v3 + v4

formative ~~ formative

'

formativeModelFit <- sem(

formativeModel_syntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR",

optim.gradient = "numerical")

formativeModelParameters <- parameterEstimates(formativeModelFit)

formativeModelParametersHere are the degrees of freedom:

Code

[1] 0lavaan 0.6-20 ended normally after 7 iterations

Estimator ML

Optimization method NLMINB

Number of model parameters 7

Number of observations 75

Number of missing patterns 10

Model Test User Model:

Test statistic NA

Degrees of freedom -3

P-value (Unknown) NAHere is a model diagram:

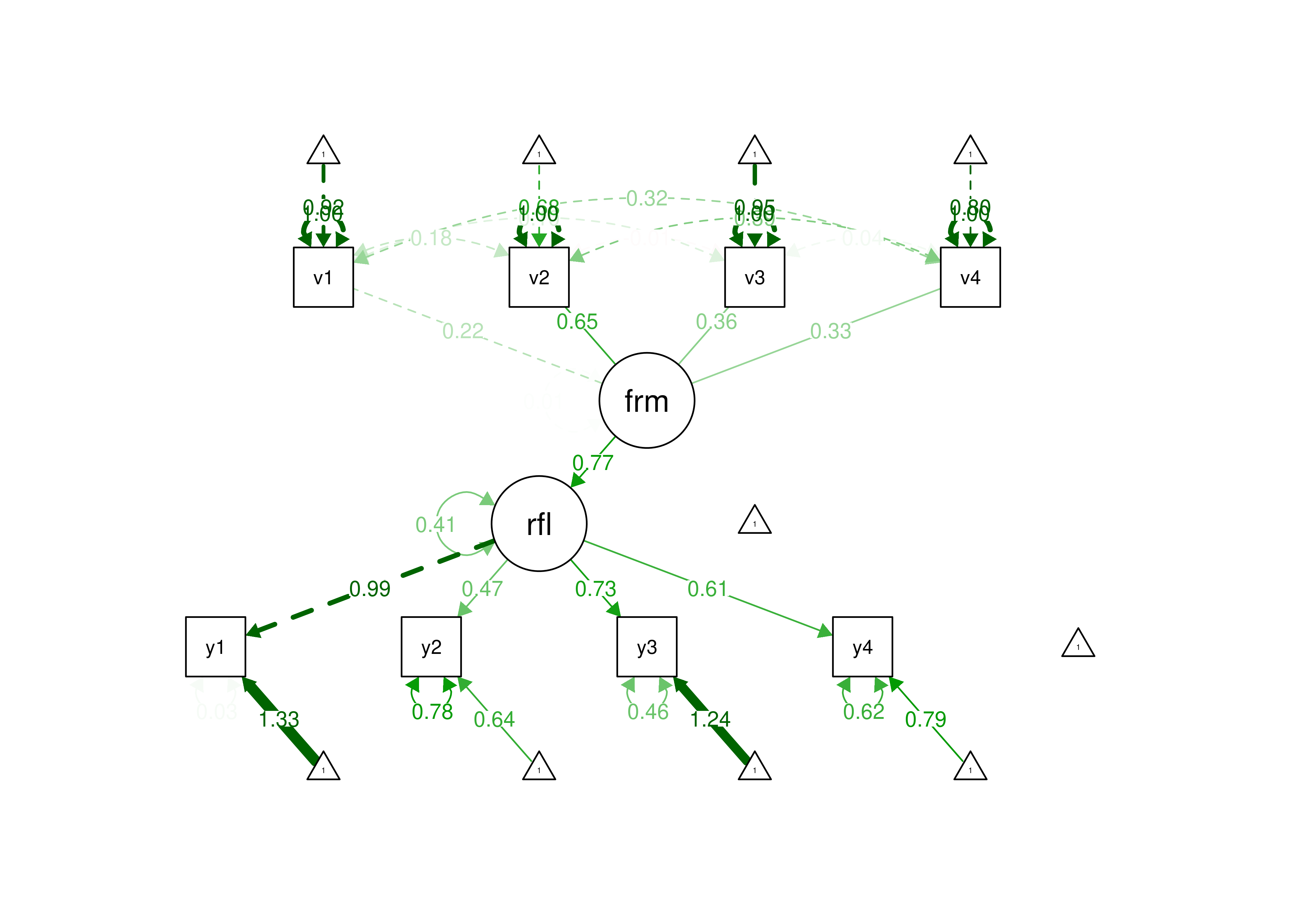

Figure 7.6: Example of an Under-Identified Formative Model.

For a formative model with 4 measures, the number of known values (14) is less than the number of parameters (19). The number of degrees of freedom is negative (\(14 - 19 = -5\)), thus the model is not able to be identified—the model is under-identified.

Thus, for a formative model, we need more parameters than we have data—the model is under-identified. Therefore, to estimate a formative model with 4 indicators, we must add assumptions and other variables that are consequences of the formative construct. Options for identifying a formative construct are described by Treiblmaier et al. (2011). See below for an example formative model that is identified because of additional assumptions.

Code

formativeModel2_syntax <- '

#Formative model factor loadings

formative <~ 1*v1 + v2 + v3 + v4

reflective =~ y1 + y2 + y3 + y4

formative ~~ 1*formative

reflective ~ formative

'

formativeModel2Fit <- sem(

formativeModel2_syntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR",

optim.gradient = "numerical")

formativeModel2Parameters <- parameterEstimates(formativeModel2Fit)

formativeModel2Parametersdf

14

Figure 7.7: Example of an Identified Formative Model.

Thus, formative constructs are challenging to use in a SEM framework. To estimate a formative construct in a SEM framework, the formative construct must be used in the context of a model that allows some constraints. A formative latent factor includes a disturbance term, and is thus not entirely determined by the causal indicators (Bollen & Bauldry, 2011). A composite (such as in principal component analysis), by contrast, has no disturbance term and is therefore completely determined by the composite indicators (Bollen & Bauldry, 2011). Emerging techniques such as confirmatory composite analysis allow estimation of formative composites (Schuberth, 2023; Yu et al., 2023).

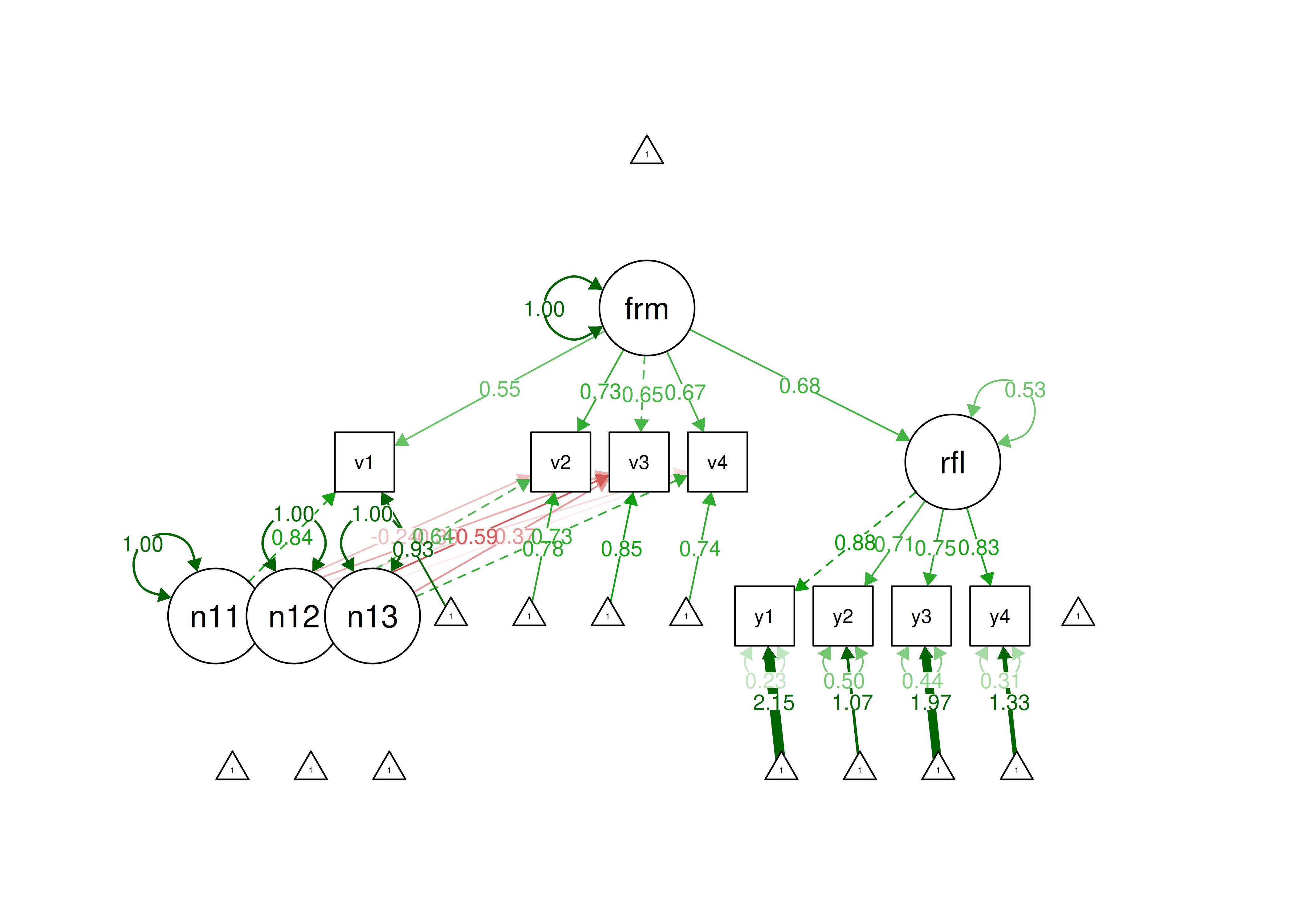

Below is an example of confirmatory composite analysis using the Henseler-Ogasawara specification (adapted from: https://confirmatorycompositeanalysis.com/tutorials-lavaan; archived at: https://perma.cc/7LSU-PTZR) (Schuberth, 2023):

Code

formativeModel3_syntax <- '

# Specification of the reflective latent factor

reflective =~ y1 + y2 + y3 + y4

# Specification of the associations between the observed variables v1 - v4

# and the emergent variable "formative" in terms of composite loadings.

formative =~ NA*v1 + l11*v1+ l21*v2 + 1*v3 + l41*v4

# Label the variance of the formative composite

formative ~~ varformative*formative

# Specification of the associations between the observed variables v1 - v4

# and their excrescent variables in terms of composite loadings.

nu11 =~ 1*v1 + l22*v2 + l32*v3 + l42*v4

nu12 =~ 0*v1 + 1*v2 + l33*v3 + l43*v4

nu13 =~ 0*v1 + 0*v2 + l34*v3 + 1*v4

# Label the variances of the excrescent variables

nu11 ~~ varnu11*nu11

nu12 ~~ varnu12*nu12

nu13 ~~ varnu13*nu13

# Specify the effect of formative on reflective

reflective ~ formative

# The H-O specification assumes that the excrescent variables are uncorrelated.

# Therefore, the covariance between the excrescent variables is fixed to 0:

nu11 ~~ 0*nu12 + 0*nu13

nu12 ~~ 0*nu13

# Moreover, the H-O specification assumes that the excrescent variables are uncorrelated

# with the emergent and latent variables. Therefore, the covariances between

# the emergent and the excrescent varibales are fixed to 0:

formative ~~ 0*nu11 + 0*nu12 + 0*nu13

reflective =~ 0*nu11 + 0*nu12 + 0*nu13

# In lavaan, the =~ command is originally used to specify a common factor model,

# which assumes that each observed variable is affected by a random measurement error.

# It is assumed that the observed variables forming composites are free from

# random measurement error. Therefore, the variances of the random measurement errors

# originally attached to the observed variables by the common factor model are fixed to 0:

v1 ~~ 0*v1

v2 ~~ 0*v2

v3 ~~ 0*v3

v4 ~~ 0*v4

# Calculate the unstandardized weights to form the formative latent variable

w1 := (-l32 + l22*l33 + l34*l42 - l22*l34*l43)/(1 -

l11*l32 - l21*l33 + l11*l22*l33 - l34*l41 + l11*l34*l42 +

l21* l34* l43 - l11* l22* l34* l43)

w2 := (-l33 + l34*l43)/(1 - l11*l32 - l21*l33 +

l11*l22*l33 - l34*l41 + l11*l34*l42 + l21*l34*l43 - l11*l22*l34*l43)

w3 := 1/(1 - l11*l32 - l21*l33 + l11*l22*l33 -

l34*l41 + l11*l34*l42 + l21*l34*l43 - l11*l22*l34*l43)

w4 := -l34/(1 - l11*l32 - l21*l33 + l11*l22*l33 -

l34*l41 + l11*l34*l42 + l21*l34*l43 - l11*l22*l34*l43)

# Calculate the variances

varv1 := l11^2*varformative + varnu11

varv2 := l21^2*varformative + l22^2*varnu11 + varnu12

varv3 := varformative + l32^2*varnu11 + l33^2*varnu12 + l34^2*varnu13

varv4 := l41^2*varformative + l42^2*varnu11 + l43^2*varnu12 + varnu13

# Calculate the standardized weights to form the formative latent variable

w1std := w1*(varv1/varformative)^(1/2)

w2std := w2*(varv2/varformative)^(1/2)

w3std := w3*(varv3/varformative)^(1/2)

w4std := w4*(varv4/varformative)^(1/2)

'

formativeModel3Fit <- sem(

formativeModel3_syntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR")

formativeModel3Parameters <- parameterEstimates(formativeModel3Fit)

formativeModel3Parametersdf

14

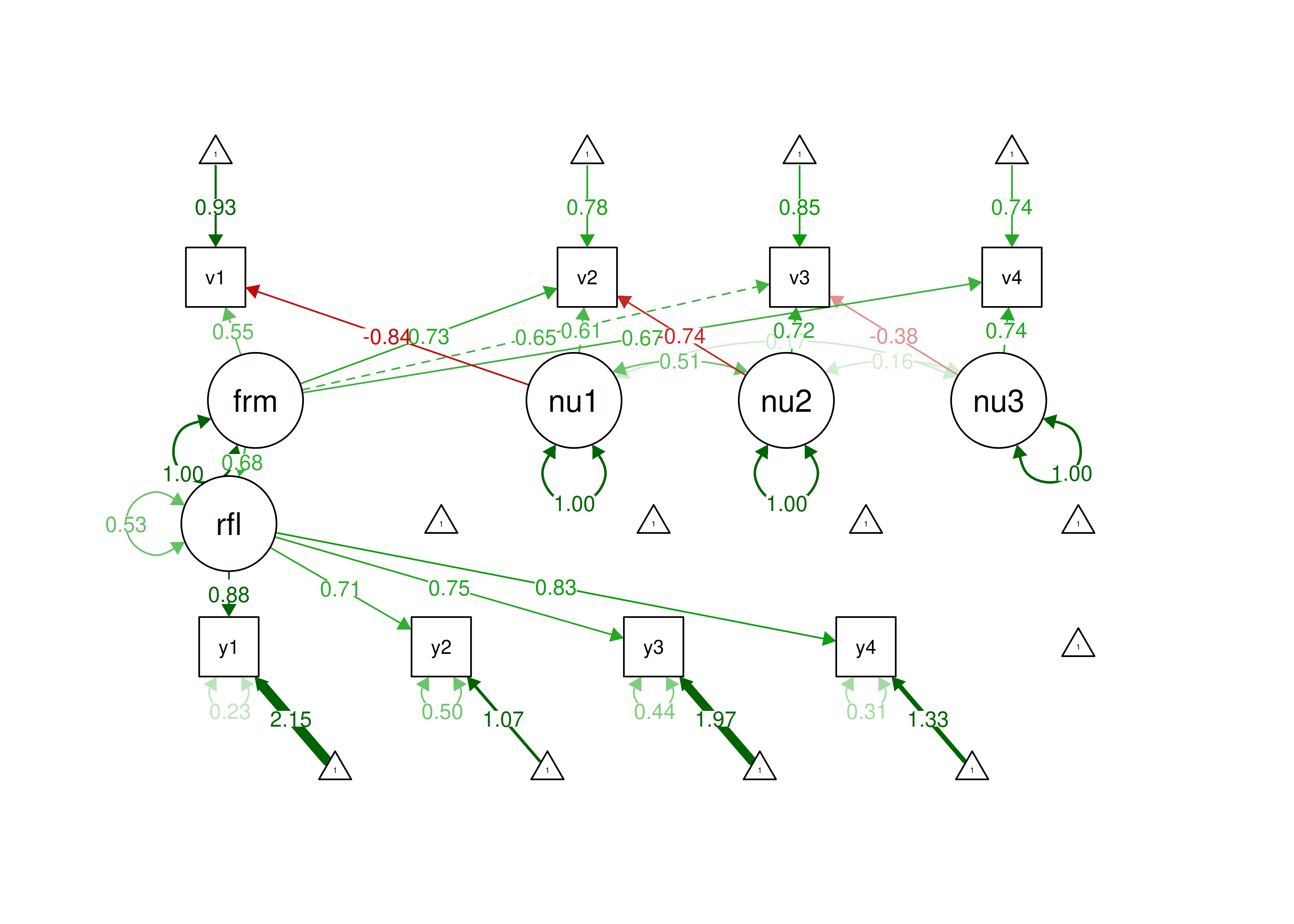

Below is an example of confirmatory composite analysis using the refined Henseler-Ogasawara specification (Yu et al., 2023):

Code

formativeModel4_syntax <- '

# Specification of the reflective latent factor

reflective =~ y1 + y2 + y3 + y4

# Specification of the associations between the observed variables v1 - v4

# and the emergent variable "formative" in terms of composite loadings.

formative =~ NA*v1 + l11*v1 + l21*v2 + 1*v3 + l41*v4

# Label the variance of the formative composite

formative ~~ varformative*formative

# Specification of the associations between the observed variables v1 - v4

# and their excrescent variables in terms of composite loadings.

nu1 =~ 1*v2 + l12*v1

nu2 =~ 1*v3 + l23*v2

nu3 =~ 1*v4 + l34*v3

# Label the variances of the excrescent variables

nu1 ~~ varnu1*nu1

nu2 ~~ varnu2*nu2

nu3 ~~ varnu3*nu3

# Specify the effect of formative on reflective

reflective ~ formative

# Constrain the covariances between excrescent variables and

# other variables in the structural model to zero. Moreover,

# label the covariances among excrescent variables.

nu1 ~~ 0*formative + 0*reflective + cov12*nu2 + cov13*nu3

nu2 ~~ 0*formative + 0*reflective + cov23*nu3

nu3 ~~ 0*formative + 0*reflective

# Fix the variances of the disturbance terms to zero.

v1 ~~ 0*v1

v2 ~~ 0*v2

v3 ~~ 0*v3

v4 ~~ 0*v4

# Calculate the unstandardized weights to form the formative latent variable

w1 := ((1)*((1)*((1)))) / ((l11)*((1)*((1)*((1)))) + -(l21)*((l12)*((1)*((1)))) + (1)*((l12)*((l23)*((1)))) + -(l41)*((l12)*((l23)*((l34)))))

w2 := -((l12)*((1)*((1)))) / ((l11)*((1)*((1)*((1)))) + -(l21)*((l12)*((1)*((1)))) + (1)*((l12)*((l23)*((1)))) + -(l41)*((l12)*((l23)*((l34)))))

w3 := ((l12)*((l23)*((1)))) / ((l11)*((1)*((1)*((1)))) + -(l21)*((l12)*((1)*((1)))) + (1)*((l12)*((l23)*((1)))) + -(l41)*((l12)*((l23)*((l34)))))

w4 := -((l12)*((l23)*((l34)))) / ((l11)*((1)*((1)*((1)))) + -(l21)*((l12)*((1)*((1)))) + (1)*((l12)*((l23)*((1)))) + -(l41)*((l12)*((l23)*((l34)))))

# Calculate the variances

varv1 := ((l11) * (varformative)) * (l11) + ((l12) * (varnu1)) * (l12)

varv2 := ((l21) * (varformative)) * (l21) + ((1) * (varnu1) + (l23) * (cov12)) * (1) + ((1) * (cov12) + (l23) * (varnu2)) * (l23)

varv3 := ((1) * (varformative)) * (1) + ((1) * (varnu2) + (l34) * (cov23)) * (1) + ((1) * (cov23) + (l34) * (varnu3)) * (l34)

varv4 := ((l41) * (varformative)) * (l41) + ((1) * (varnu3)) * (1)

# Calculate the standardized weights to form the formative latent variable

wstdv1 := ((w1) * (sqrt(varv1))) * (1/sqrt(varformative))

wstdv2 := ((w2) * (sqrt(varv2))) * (1/sqrt(varformative))

wstdv3 := ((w3) * (sqrt(varv3))) * (1/sqrt(varformative))

wstdv4 := ((w4) * (sqrt(varv4))) * (1/sqrt(varformative))

'

formativeModel4Fit <- sem(

formativeModel4_syntax,

data = PoliticalDemocracy,

missing = "ML",

estimator = "MLR")

formativeModel4Parameters <- parameterEstimates(formativeModel4Fit)

formativeModel4Parametersdf

14

You can generate the weights for the indicators (to be used in the model syntax) for the refined Henseler-Ogasawara specification using the following code:

Code

library("calculus")

# First, construct the loading matrix

loadingMatrix <- matrix(c('l11','l21',1,'l41','l12',1,0,0,0,'l23',1,0,0,0,'l34',1),4,4)

# Check the structure

loadingMatrix

# Invert matrix, the first row contains the (unstandardized) weights

# these can be copy and pasted to the lavaan model to specify the weights as new parameters

mxinv(loadingMatrix)Florian Schubert provides an R function to create the full lavaan syntax for confirmatory composite analysis at the following link: https://github.com/FloSchuberth/HOspecification

7.5 Additional Types of SEM

Up to this point, we have discussed SEM with dimensional constructs. It also worth knowing about additional types of SEM models, including latent class models and mixture models, that handle categorical constructs. However, most disorders are more accurately conceptualized as dimensional than as categorical (Markon et al., 2011), so just because you can estimate categorical latent factors does not necessarily mean that one should.

7.5.1 Latent Class Models

In latent class models, the construct is not dimensional, but rather categorical. The categorical constructs are latent classifications and are called latent classes. For instance, the construct could be a diagnosis that influences scores on the measures. Latent class models examine qualitative differences in kind, rather than quantitative differences in degree.

7.5.2 Mixture Models

Mixture models allow for a combination of latent categorical constructs (classes) and latent dimensional constructs. That is, it allows for both qualitative and quantitative differences. However, this additional model complexity also necessitates a larger sample size for estimation. SEM generally requires a 3-digit sample size (\(N = 100+\)), whereas mixture models typically require a 4- or 5-digit sample size (\(N = 1,000+\)).

7.5.3 Exploratory Structural Equation Models

We describe exploratory structural equation models in Section 14.1.4.3.3.

7.6 Causal Diagrams: Directed Acyclic Graphs

A key tool when designing a structural equation model is a conceptual depiction of the hypothesized causal processes.

A causal diagram depicts the hypothesized causal processes that link two or more variables.

A common form of causal diagrams is the directed acyclic graph (DAG).

DAGs provide a helpful tool to communicate about causal questions and help identify how to avoid bias (i.e., over-estimation) in associations between variables due to confounding (i.e., common causes) (Digitale et al., 2022).

Free tools to create DAGs include the R package dagitty (Textor et al., 2017) and the associated browser-based extension, DAGitty: https://dagitty.net (archived at https://perma.cc/U9BY-VZE2).

Path analytic diagrams (i.e., causal diagrams with boxes, circles, and lines) are described in Section 4.1.1 of Chapter 4.

Karch (in press) provides a tool to create lavaan R syntax from a path analytic diagram: https://lavaangui.org.

7.7 Model Fit Indices

Various model fit indices can be used for evaluating how well a model fits the data and for comparing the fit of two competing models. Fit indices known as absolute fit indices compare whether the model fits better than the best-possible fitting model (i.e., a saturated model). Examples of absolute fit indices include the chi-square test, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR).

The chi-square test evaluates whether the model has a significant degree of misfit relative to the best-possible fitting model (a saturated model that fits as many parameters as possible; i.e., as many parameters as there are degrees of freedom); the null hypothesis of a chi-square test is that there is no difference between the predicted data (i.e., the data that would be observed if the model were true) and the observed data. Thus, a non-significant chi-square test indicates good model fit. However, because the null hypothesis of the chi-square test is that the model-implied covariance matrix is exactly equal to the observed covariance matrix (i.e., a model of perfect fit), this may be an unrealistic comparison. Models are simplifications of reality, and our models are virtually never expected to be a perfect description of reality. Thus, we would say a model is “useful” and partially validated if “it helps us to understand the relation between variables and does a ‘reasonable’ job of matching the data…A perfect fit may be an inappropriate standard, and a high chi-square estimate may indicate what we already know—that the hypothesized model holds approximately, not perfectly.” (Bollen, 1989, p. 268). The power of the chi-square test depends on sample size, and a large sample will likely detect small differences as significantly worse than the best-possible fitting model (Bollen, 1989).

RMSEA is an index of absolute fit. Lower values indicate better fit.

SRMR is an index of absolute fit with no penalty for model complexity. Lower values indicate better fit.

There are also various fit indices known as incremental, comparative, or relative fit indices that compare whether the model fits better than the worst-possible fitting model (i.e., a “baseline” or “null” model). Incremental fit indices include a chi-square difference test, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). Unlike the chi-square test comparing the model to the best-possible fitting model, a significant chi-square test of the relative fit index indicates better fit—i.e., that the model fits better than the worst-possible fitting model.

CFI is another relative fit index that compares the model to the worst-possible fitting model. Higher values indicate better fit.

TLI is another relative fit index. Higher values indicate better fit.

Parsimony fit include fit indices that use information criteria fit indices, including the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). BIC penalizes model complexity more so than AIC. Lower AIC and BIC values indicate better fit.

Chi-square difference tests and CFI can be used to compare two nested models. AIC and BIC can be used to compare two non-nested models.

Criteria for acceptable fit and good fit of SEM models are in Table 7.1.

In addition, dynamic fit indexes have been proposed based on simulation to identify fit index cutoffs that are tailored to the characteristics of the specific model and data (McNeish, 2026; McNeish & Wolf, 2023); dyanmic fit indexes are available via the dynamic package in R or with a webapp.

| SEM Fit Index | Acceptable Fit | Good Fit |

|---|---|---|

| RMSEA | \(\leq\) .08 | \(\leq\) .05 |

| CFI | \(\geq\) .90 | \(\geq\) .95 |

| TLI | \(\geq\) .90 | \(\geq\) .95 |

| SRMR | \(\leq\) .10 | \(\leq\) .08 |

However, good model fit does not necessarily indicate a true model.

In addition to global fit indices, it can also be helpful to examine evidence of local fit (Kline, 2023; McNeish, 2026), such as the residual covariance matrix. The residual covariance matrix represents the difference between the observed covariance matrix and the model-implied covariance matrix (the observed covariance matrix minus the model-implied covariance matrix). These difference values are called covariance residuals. Standardizing the covariance matrix by converting each to a correlation matrix can be helpful for interpreting the magnitude of any local misfit. This is known as a residual correlation matrix, which is composed of correlation residuals. Correlation residuals greater than |.10| are possible evidence for poor local fit (Kline, 2023). If a correlation residual is positive, it suggests that the model underpredicts the observed association between the two variables (i.e., the observed covariance is greater than the model-implied covariance). If a correlation residual is negative, it suggests that the model overpredicts their observed association between the two variables (i.e., the observed covariance is smaller than the model-implied covariance). If the two variables are connected by only indirect pathways, it may be helpful to respecify the model with direct pathways between the two variables, such as a direct effect (i.e., regression path) or a covariance path. For guidance on evaluating local fit, see Kline (2024).

7.8 Correlation Matrix

measure1 measure2 measure3

measure1 1.0000000 0.5444728 0.6782616

measure2 0.5444728 1.0000000 0.7766733

measure3 0.6782616 0.7766733 1.0000000Correlation matrices of various types using the cor.table() function from the petersenlab package (Petersen, 2025) are in Tables 7.2, 7.3, and 7.4.

Code

| measure1 | measure2 | measure3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. measure1.r | 1.00 | .54*** | .68*** |

| 2. sig | NA | .00 | .00 |

| 3. n | 298 | 297 | 298 |

| 4. measure2.r | .54*** | 1.00 | .78*** |

| 5. sig | .00 | NA | .00 |

| 6. n | 297 | 298 | 298 |

| 7. measure3.r | .68*** | .78*** | 1.00 |

| 8. sig | .00 | .00 | NA |

| 9. n | 298 | 298 | 299 |

| measure1 | measure2 | measure3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. measure1 | 1.00 | ||

| 2. measure2 | .54*** | 1.00 | |

| 3. measure3 | .68*** | .78*** | 1.00 |

| measure1 | measure2 | measure3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. measure1 | 1.00 | ||

| 2. measure2 | .54 | 1.00 | |

| 3. measure3 | .68 | .78 | 1.00 |

7.9 Measurement Model (of a Given Construct)

Even though CFA models are measurement models, I provide separate examples of a measurement model and CFA models in my examples because CFA is often used to test competing factor structures. For instance, you could use CFA to test whether the variance in several measures’ scores is best explained with one factor or two factors. In the measurement model below, I present a simple one-factor model with three measures. The measurement model is what we settle on as the estimation of each construct before we add the structural component to estimate the relations among latent variables. Basically, we add the structural component onto the measurement model. In Section 7.10, I present a CFA model with multiple latent factors.

The measurement models were fit in the lavaan package (Rosseel et al., 2022).

7.9.1 Specify the Model

Code

measurementModel_syntax <- '

#Factor loadings

latentFactor =~ measure1 + measure2 + measure3

'

measurementModel_fullSyntax <- '

#Factor loadings (free the factor loading of the first indicator)

latentFactor =~ NA*measure1 + measure2 + measure3

#Fix latent mean to zero

latentFactor ~ 0

#Fix latent variance to one

latentFactor ~~ 1*latentFactor

#Estimate covariances among latent variables (not applicable because there is only one latent variable)

#Estimate residual variances of manifest variables

measure1 ~~ measure1

measure2 ~~ measure2

measure3 ~~ measure3

#Free intercepts of manifest variables

measure1 ~ int1*1

measure2 ~ int2*1

measure3 ~ int3*1

'7.9.3 Display Summary Output

This measurement model with three indicators is just-identified—the number of parameters estimated is equal to the number of known values, thus leaving 0 degrees of freedom. In the model, all three indicators load strongly on the latent factor (measure 1: \(\beta = 0.69\); measure 2: \(\beta = 0.79\); measure 3: \(\beta = 0.98\)). Thus, the loadings of this measurement model would be consistent with a reflective latent construct. In terms of interpretation, all three indicators loaded positively on the latent factor, so higher levels of the latent factor are indicated by higher levels on the indicators. However, one of the estimated observed variances is negative, so the model is not able to be estimated accurately. Thus, we would need to make additional adjustments in order to estimate the model.

lavaan 0.6-20 ended normally after 23 iterations

Estimator ML

Optimization method NLMINB

Number of model parameters 9

Used Total

Number of observations 299 300

Number of missing patterns 3

Model Test User Model:

Standard Scaled

Test Statistic 0.000 0.000

Degrees of freedom 0 0

Model Test Baseline Model:

Test statistic 459.500 389.896

Degrees of freedom 3 3

P-value 0.000 0.000

Scaling correction factor 1.179

User Model versus Baseline Model:

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 1.000 1.000

Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 1.000 1.000

Robust Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 1.000

Robust Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 1.000

Loglikelihood and Information Criteria:

Loglikelihood user model (H0) -3588.224 -3588.224

Loglikelihood unrestricted model (H1) -3588.224 -3588.224

Akaike (AIC) 7194.449 7194.449

Bayesian (BIC) 7227.753 7227.753

Sample-size adjusted Bayesian (SABIC) 7199.210 7199.210

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation:

RMSEA 0.000 NA

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.000 NA

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.000 NA

P-value H_0: RMSEA <= 0.050 NA NA

P-value H_0: RMSEA >= 0.080 NA NA

Robust RMSEA 0.000

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.000

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.000

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA <= 0.050 NA

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA >= 0.080 NA

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual:

SRMR 0.000 0.000

Parameter Estimates:

Standard errors Sandwich

Information bread Observed

Observed information based on Hessian

Latent Variables:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

latentFactor =~

measure1 7.198 0.575 12.525 0.000 7.198 0.689

measure2 13.487 0.855 15.780 0.000 13.487 0.789

measure3 28.122 1.343 20.943 0.000 28.122 0.984

Intercepts:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

.measure1 50.136 0.605 82.859 0.000 50.136 4.797

.measure2 50.489 0.990 51.024 0.000 50.489 2.952

.measure3 99.720 1.652 60.361 0.000 99.720 3.491

Variances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

.measure1 57.444 5.116 11.228 0.000 57.444 0.526

.measure2 110.536 12.756 8.665 0.000 110.536 0.378

.measure3 25.203 42.395 0.594 0.552 25.203 0.031

latentFactor 1.000 1.000 1.000

R-Square:

Estimate

measure1 0.474

measure2 0.622

measure3 0.969lavaan 0.6-20 ended normally after 23 iterations

Estimator ML

Optimization method NLMINB

Number of model parameters 9

Used Total

Number of observations 299 300

Number of missing patterns 3

Model Test User Model:

Standard Scaled

Test Statistic 0.000 0.000

Degrees of freedom 0 0

Model Test Baseline Model:

Test statistic 459.500 389.896

Degrees of freedom 3 3

P-value 0.000 0.000

Scaling correction factor 1.179

User Model versus Baseline Model:

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 1.000 1.000

Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 1.000 1.000

Robust Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 1.000

Robust Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 1.000

Loglikelihood and Information Criteria:

Loglikelihood user model (H0) -3588.224 -3588.224

Loglikelihood unrestricted model (H1) -3588.224 -3588.224

Akaike (AIC) 7194.449 7194.449

Bayesian (BIC) 7227.753 7227.753

Sample-size adjusted Bayesian (SABIC) 7199.210 7199.210

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation:

RMSEA 0.000 NA

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.000 NA

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.000 NA

P-value H_0: RMSEA <= 0.050 NA NA

P-value H_0: RMSEA >= 0.080 NA NA

Robust RMSEA 0.000

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.000

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.000

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA <= 0.050 NA

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA >= 0.080 NA

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual:

SRMR 0.000 0.000

Parameter Estimates:

Standard errors Sandwich

Information bread Observed

Observed information based on Hessian

Latent Variables:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

latentFactor =~

measure1 7.198 0.575 12.525 0.000 7.198 0.689

measure2 13.487 0.855 15.780 0.000 13.487 0.789

measure3 28.122 1.343 20.943 0.000 28.122 0.984

Intercepts:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

ltntFct 0.000 0.000 0.000

.measur1 (int1) 50.136 0.605 82.859 0.000 50.136 4.797

.measur2 (int2) 50.489 0.990 51.024 0.000 50.489 2.952

.measur3 (int3) 99.720 1.652 60.361 0.000 99.720 3.491

Variances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

latentFactor 1.000 1.000 1.000

.measure1 57.444 5.116 11.228 0.000 57.444 0.526

.measure2 110.536 12.756 8.665 0.000 110.536 0.378

.measure3 25.203 42.395 0.594 0.552 25.203 0.031

R-Square:

Estimate

measure1 0.474

measure2 0.622

measure3 0.9697.9.4 Estimates of Model Fit

You can extract specific fit indices using the following syntax:

Code

chisq df pvalue

0.0 0.0 NA

chisq.scaled df.scaled pvalue.scaled

0.0 0.0 NA

chisq.scaling.factor baseline.chisq baseline.df

NA 459.5 3.0

baseline.pvalue rmsea cfi

0.0 0.0 1.0

tli srmr rmsea.robust

1.0 0.0 0.0

cfi.robust tli.robust

1.0 1.0 Because the model is just-identified, many fit statistics are not able to be estimated.

7.9.5 Residuals

$type

[1] "cor.bollen"

$cov

measr1 measr2 measr3

measure1 0

measure2 0 0

measure3 0 0 0

$mean

measure1 measure2 measure3

0 0 0 7.9.8 Internal Consistency Reliability

Internal consistency reliability of items composing the latent factors, as quantified by omega (\(\omega\)) and average variance extracted (AVE), was estimated using the semTools package (Jorgensen et al., 2021).

latentFactor

0.925 latentFactor

0.841 7.10 Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models were fit in the lavaan package (Rosseel et al., 2022).

The examples were adapted from the lavaan documentation: https://lavaan.ugent.be/tutorial/cfa.html (archived at https://perma.cc/GKY3-9YE4).

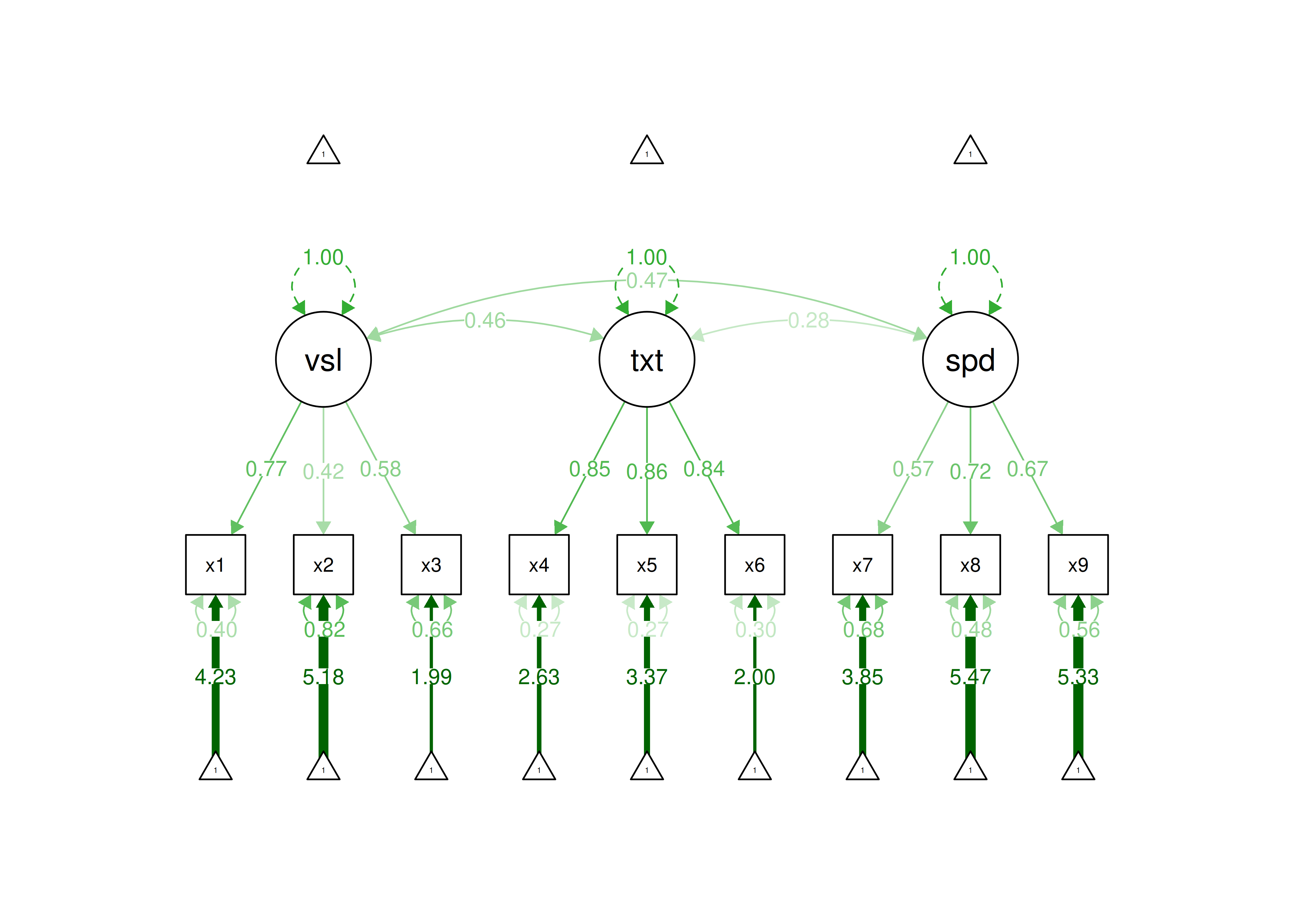

In this CFA model, we estimate three latent factors with three indicators loading on each latent factor.

7.10.1 Specify the Model

Code

cfaModel_syntax <- '

#Factor loadings

visual =~ x1 + x2 + x3

textual =~ x4 + x5 + x6

speed =~ x7 + x8 + x9

'

cfaModel_fullSyntax <- '

#Factor loadings (free the factor loading of the first indicator)

visual =~ NA*x1 + x2 + x3

textual =~ NA*x4 + x5 + x6

speed =~ NA*x7 + x8 + x9

#Fix latent means to zero

visual ~ 0

textual ~ 0

speed ~ 0

#Fix latent variances to one

visual ~~ 1*visual

textual ~~ 1*textual

speed ~~ 1*speed

#Estimate covariances among latent variables

visual ~~ textual

visual ~~ speed

textual ~~ speed

#Estimate residual variances of manifest variables

x1 ~~ x1

x2 ~~ x2

x3 ~~ x3

x4 ~~ x4

x5 ~~ x5

x6 ~~ x6

x7 ~~ x7

x8 ~~ x8

x9 ~~ x9

#Free intercepts of manifest variables

x1 ~ int1*1

x2 ~ int2*1

x3 ~ int3*1

x4 ~ int4*1

x5 ~ int5*1

x6 ~ int6*1

x7 ~ int7*1

x8 ~ int8*1

x9 ~ int9*1

'7.10.3 Display Summary Output

In this model, all nine indicators load strongly on their respective latent factor. Thus, this measurement model would be defensible. In terms of interpretation, all indicators load positively on their respective latent factor, so higher levels of the latent factor are indicated by higher levels on the indicators.

lavaan 0.6-20 ended normally after 42 iterations

Estimator ML

Optimization method NLMINB

Number of model parameters 30

Number of observations 301

Number of missing patterns 1

Model Test User Model:

Standard Scaled

Test Statistic 85.306 87.132

Degrees of freedom 24 24

P-value (Chi-square) 0.000 0.000

Scaling correction factor 0.979

Yuan-Bentler correction (Mplus variant)

Model Test Baseline Model:

Test statistic 918.852 880.082

Degrees of freedom 36 36

P-value 0.000 0.000

Scaling correction factor 1.044

User Model versus Baseline Model:

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.931 0.925

Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 0.896 0.888

Robust Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.932

Robust Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 0.897

Loglikelihood and Information Criteria:

Loglikelihood user model (H0) -3737.745 -3737.745

Scaling correction factor 1.093

for the MLR correction

Loglikelihood unrestricted model (H1) -3695.092 -3695.092

Scaling correction factor 1.043

for the MLR correction

Akaike (AIC) 7535.490 7535.490

Bayesian (BIC) 7646.703 7646.703

Sample-size adjusted Bayesian (SABIC) 7551.560 7551.560

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation:

RMSEA 0.092 0.093

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.071 0.073

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.114 0.115

P-value H_0: RMSEA <= 0.050 0.001 0.001

P-value H_0: RMSEA >= 0.080 0.840 0.862

Robust RMSEA 0.091

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.070

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.113

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA <= 0.050 0.001

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA >= 0.080 0.820

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual:

SRMR 0.060 0.060

Parameter Estimates:

Standard errors Sandwich

Information bread Observed

Observed information based on Hessian

Latent Variables:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

visual =~

x1 0.900 0.100 8.973 0.000 0.900 0.772

x2 0.498 0.088 5.681 0.000 0.498 0.424

x3 0.656 0.080 8.151 0.000 0.656 0.581

textual =~

x4 0.990 0.061 16.150 0.000 0.990 0.852

x5 1.102 0.055 20.146 0.000 1.102 0.855

x6 0.917 0.058 15.767 0.000 0.917 0.838

speed =~

x7 0.619 0.086 7.193 0.000 0.619 0.570

x8 0.731 0.093 7.875 0.000 0.731 0.723

x9 0.670 0.099 6.761 0.000 0.670 0.665

Covariances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

visual ~~

textual 0.459 0.073 6.258 0.000 0.459 0.459

speed 0.471 0.119 3.954 0.000 0.471 0.471

textual ~~

speed 0.283 0.085 3.311 0.001 0.283 0.283

Intercepts:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

.x1 4.936 0.067 73.473 0.000 4.936 4.235

.x2 6.088 0.068 89.855 0.000 6.088 5.179

.x3 2.250 0.065 34.579 0.000 2.250 1.993

.x4 3.061 0.067 45.694 0.000 3.061 2.634

.x5 4.341 0.074 58.452 0.000 4.341 3.369

.x6 2.186 0.063 34.667 0.000 2.186 1.998

.x7 4.186 0.063 66.766 0.000 4.186 3.848

.x8 5.527 0.058 94.854 0.000 5.527 5.467

.x9 5.374 0.058 92.546 0.000 5.374 5.334

Variances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

.x1 0.549 0.156 3.509 0.000 0.549 0.404

.x2 1.134 0.112 10.135 0.000 1.134 0.821

.x3 0.844 0.100 8.419 0.000 0.844 0.662

.x4 0.371 0.050 7.382 0.000 0.371 0.275

.x5 0.446 0.057 7.870 0.000 0.446 0.269

.x6 0.356 0.047 7.658 0.000 0.356 0.298

.x7 0.799 0.097 8.222 0.000 0.799 0.676

.x8 0.488 0.120 4.080 0.000 0.488 0.477

.x9 0.566 0.119 4.768 0.000 0.566 0.558

visual 1.000 1.000 1.000

textual 1.000 1.000 1.000

speed 1.000 1.000 1.000

R-Square:

Estimate

x1 0.596

x2 0.179

x3 0.338

x4 0.725

x5 0.731

x6 0.702

x7 0.324

x8 0.523

x9 0.442lavaan 0.6-20 ended normally after 42 iterations

Estimator ML

Optimization method NLMINB

Number of model parameters 30

Number of observations 301

Number of missing patterns 1

Model Test User Model:

Standard Scaled

Test Statistic 85.306 87.132

Degrees of freedom 24 24

P-value (Chi-square) 0.000 0.000

Scaling correction factor 0.979

Yuan-Bentler correction (Mplus variant)

Model Test Baseline Model:

Test statistic 918.852 880.082

Degrees of freedom 36 36

P-value 0.000 0.000

Scaling correction factor 1.044

User Model versus Baseline Model:

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.931 0.925

Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 0.896 0.888

Robust Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.932

Robust Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 0.897

Loglikelihood and Information Criteria:

Loglikelihood user model (H0) -3737.745 -3737.745

Scaling correction factor 1.093

for the MLR correction

Loglikelihood unrestricted model (H1) -3695.092 -3695.092

Scaling correction factor 1.043

for the MLR correction

Akaike (AIC) 7535.490 7535.490

Bayesian (BIC) 7646.703 7646.703

Sample-size adjusted Bayesian (SABIC) 7551.560 7551.560

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation:

RMSEA 0.092 0.093

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.071 0.073

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.114 0.115

P-value H_0: RMSEA <= 0.050 0.001 0.001

P-value H_0: RMSEA >= 0.080 0.840 0.862

Robust RMSEA 0.091

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.070

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.113

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA <= 0.050 0.001

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA >= 0.080 0.820

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual:

SRMR 0.060 0.060

Parameter Estimates:

Standard errors Sandwich

Information bread Observed

Observed information based on Hessian

Latent Variables:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

visual =~

x1 0.900 0.100 8.973 0.000 0.900 0.772

x2 0.498 0.088 5.681 0.000 0.498 0.424

x3 0.656 0.080 8.151 0.000 0.656 0.581

textual =~

x4 0.990 0.061 16.150 0.000 0.990 0.852

x5 1.102 0.055 20.146 0.000 1.102 0.855

x6 0.917 0.058 15.767 0.000 0.917 0.838

speed =~

x7 0.619 0.086 7.193 0.000 0.619 0.570

x8 0.731 0.093 7.875 0.000 0.731 0.723

x9 0.670 0.099 6.761 0.000 0.670 0.665

Covariances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

visual ~~

textual 0.459 0.073 6.258 0.000 0.459 0.459

speed 0.471 0.119 3.954 0.000 0.471 0.471

textual ~~

speed 0.283 0.085 3.311 0.001 0.283 0.283

Intercepts:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

visual 0.000 0.000 0.000

textual 0.000 0.000 0.000

speed 0.000 0.000 0.000

.x1 (int1) 4.936 0.067 73.473 0.000 4.936 4.235

.x2 (int2) 6.088 0.068 89.855 0.000 6.088 5.179

.x3 (int3) 2.250 0.065 34.579 0.000 2.250 1.993

.x4 (int4) 3.061 0.067 45.694 0.000 3.061 2.634

.x5 (int5) 4.341 0.074 58.452 0.000 4.341 3.369

.x6 (int6) 2.186 0.063 34.667 0.000 2.186 1.998

.x7 (int7) 4.186 0.063 66.766 0.000 4.186 3.848

.x8 (int8) 5.527 0.058 94.854 0.000 5.527 5.467

.x9 (int9) 5.374 0.058 92.546 0.000 5.374 5.334

Variances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

visual 1.000 1.000 1.000

textual 1.000 1.000 1.000

speed 1.000 1.000 1.000

.x1 0.549 0.156 3.509 0.000 0.549 0.404

.x2 1.134 0.112 10.135 0.000 1.134 0.821

.x3 0.844 0.100 8.419 0.000 0.844 0.662

.x4 0.371 0.050 7.382 0.000 0.371 0.275

.x5 0.446 0.057 7.870 0.000 0.446 0.269

.x6 0.356 0.047 7.658 0.000 0.356 0.298

.x7 0.799 0.097 8.222 0.000 0.799 0.676

.x8 0.488 0.120 4.080 0.000 0.488 0.477

.x9 0.566 0.119 4.768 0.000 0.566 0.558

R-Square:

Estimate

x1 0.596

x2 0.179

x3 0.338

x4 0.725

x5 0.731

x6 0.702

x7 0.324

x8 0.523

x9 0.4427.10.4 Estimates of Model Fit

According to model fit estimates, the model fit is good according to SRMR and acceptable according to CFI, but the model fit is weaker according to RMSEA and TLI. Thus, we may want to consider adjustments to improve the model fit. In general, we want to make decisions regarding what parameters to estimate based on theory in conjunction with empiricism.

Code

chisq df pvalue

85.306 24.000 0.000

chisq.scaled df.scaled pvalue.scaled

87.132 24.000 0.000

chisq.scaling.factor baseline.chisq baseline.df

0.979 918.852 36.000

baseline.pvalue rmsea cfi

0.000 0.092 0.931

tli srmr rmsea.robust

0.896 0.060 0.091

cfi.robust tli.robust

0.932 0.897 7.10.5 Residuals

$type

[1] "cor.bollen"

$cov

x1 x2 x3 x4 x5 x6 x7 x8 x9

x1 0.000

x2 -0.030 0.000

x3 -0.008 0.094 0.000

x4 0.071 -0.012 -0.068 0.000

x5 -0.009 -0.027 -0.151 0.005 0.000

x6 0.060 0.030 -0.026 -0.009 0.003 0.000

x7 -0.140 -0.189 -0.084 0.037 -0.036 -0.014 0.000

x8 -0.039 -0.052 -0.012 -0.067 -0.036 -0.022 0.075 0.000

x9 0.149 0.073 0.147 0.048 0.067 0.056 -0.038 -0.032 0.000

$mean

x1 x2 x3 x4 x5 x6 x7 x8 x9

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 7.10.6 Modification Indices

Modification indices indicate potential additional parameters that could be estimated and that would improve model fit. For instance, the modification indices in Table ?? (generated from the syntax below) indicate a few additional factor loadings (i.e., cross-loadings) or correlated residuals that could substantially improve model fit. However, it is generally not recommended to blindly estimate additional parameters solely based on modification indices. Rather, it is generally advised to consider modification indices in light of theory.

7.10.8 Internal Consistency Reliability

Internal consistency reliability of items composing the latent factors, as quantified by omega (\(\omega\)) and average variance extracted (AVE), was estimated using the semTools package (Jorgensen et al., 2021).

visual textual speed

0.612 0.885 0.686 visual textual speed

0.371 0.721 0.424 7.10.9 Path Diagram

Below is a path diagram of the model generated using the semPlot package (Epskamp, 2022).

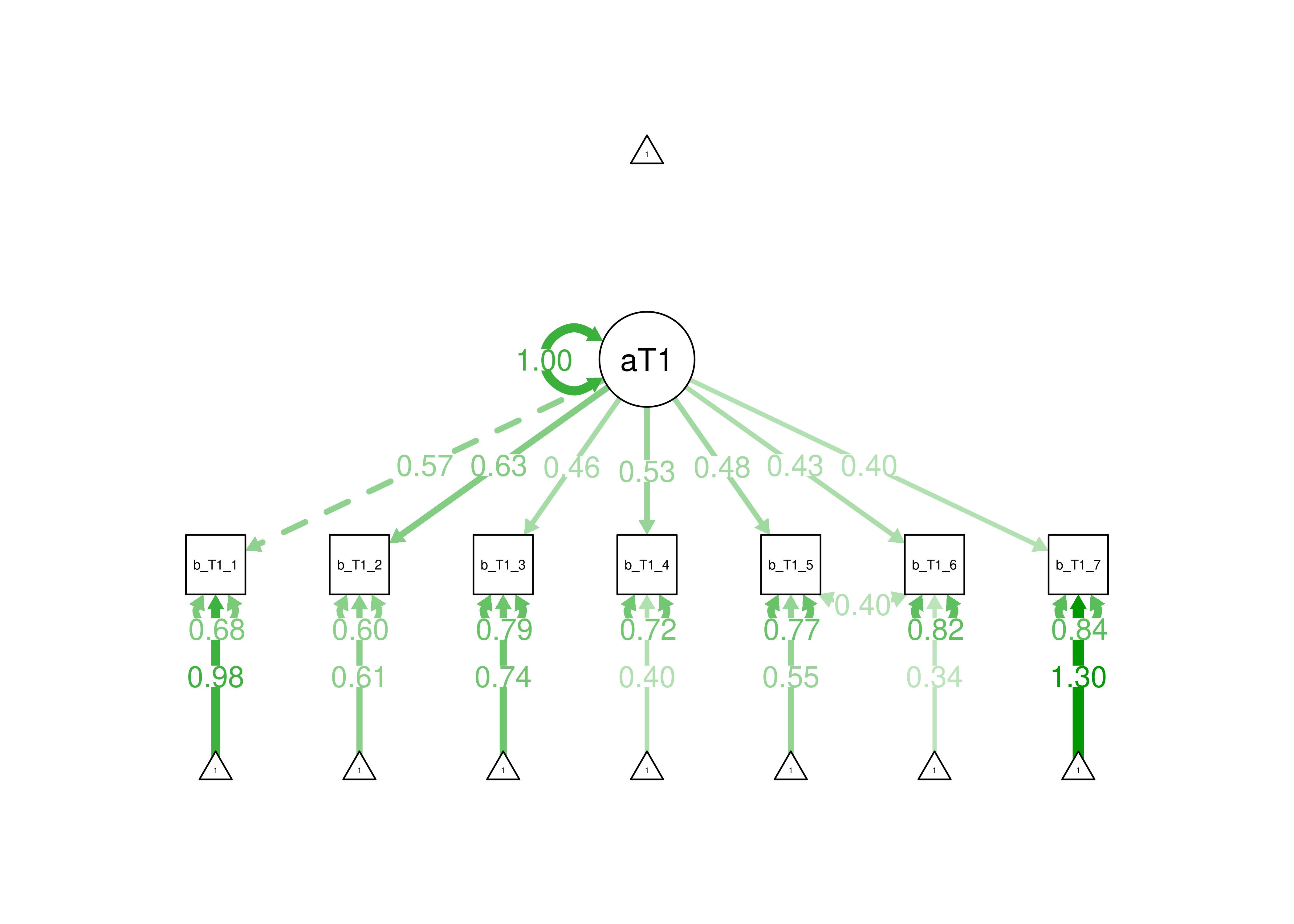

Figure 7.9: Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model.

7.10.10 Modify Model Based on Modification Indices

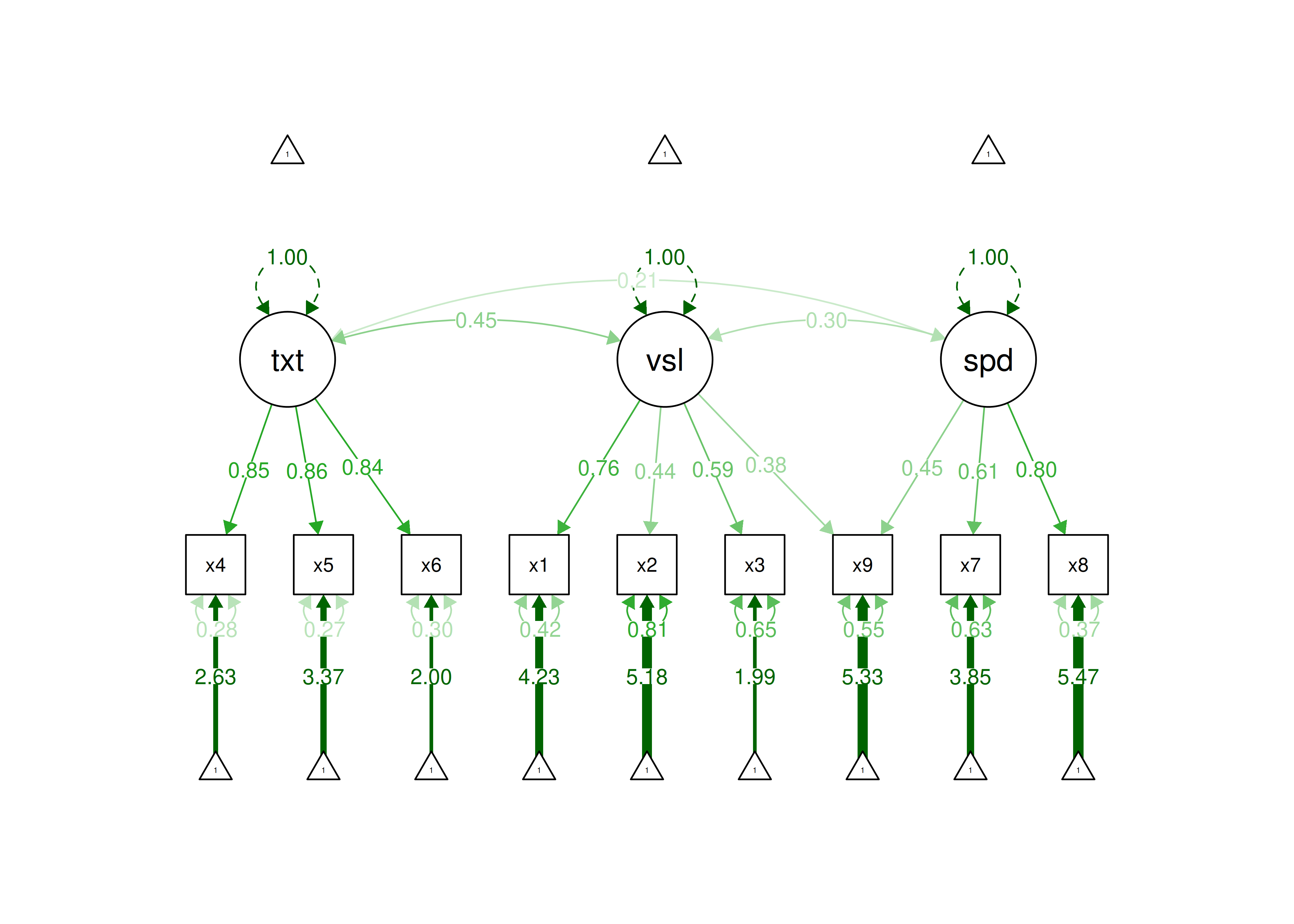

In the model below, I modified the model based on estimating an additional factor loading (assuming the additional factor loading is theoretically supported). This could be supported, for instance, if a given test involves considerable skills in both the visual domain and in speed of processing. When the same indicator loads simultaneously on two factors, this is called a cross-loading. Cross-loadings can complicate the interpretation of latent factors, as discussed in Section 14.1.4.5 of the chapter on factor analysis.

7.10.10.1 Specify the Model

Code

cfaModel2_syntax <- '

#Factor loadings

textual =~ x4 + x5 + x6

visual =~ x1 + x2 + x3 + x9

speed =~ x7 + x8 + x9

'

cfaModel2_fullSyntax <- '

#Factor loadings (free the factor loading of the first indicator)

textual =~ NA*x4 + x5 + x6

visual =~ NA*x1 + x2 + x3 + x9

speed =~ NA*x7 + x8 + x9

#Fix latent means to zero

visual ~ 0

textual ~ 0

speed ~ 0

#Fix latent variances to one

visual ~~ 1*visual

textual ~~ 1*textual

speed ~~ 1*speed

#Estimate covariances among latent variables

visual ~~ textual

visual ~~ speed

textual ~~ speed

#Estimate residual variances of manifest variables

x1 ~~ x1

x2 ~~ x2

x3 ~~ x3

x4 ~~ x4

x5 ~~ x5

x6 ~~ x6

x7 ~~ x7

x8 ~~ x8

x9 ~~ x9

#Free intercepts of manifest variables

x1 ~ int1*1

x2 ~ int2*1

x3 ~ int3*1

x4 ~ int4*1

x5 ~ int5*1

x6 ~ int6*1

x7 ~ int7*1

x8 ~ int8*1

x9 ~ int9*1

'7.10.10.3 Display Summary Output

lavaan 0.6-20 ended normally after 39 iterations

Estimator ML

Optimization method NLMINB

Number of model parameters 31

Number of observations 301

Number of missing patterns 1

Model Test User Model:

Standard Scaled

Test Statistic 52.382 51.725

Degrees of freedom 23 23

P-value (Chi-square) 0.000 0.001

Scaling correction factor 1.013

Yuan-Bentler correction (Mplus variant)

Model Test Baseline Model:

Test statistic 918.852 880.082

Degrees of freedom 36 36

P-value 0.000 0.000

Scaling correction factor 1.044

User Model versus Baseline Model:

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.967 0.966

Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 0.948 0.947

Robust Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.968

Robust Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 0.950

Loglikelihood and Information Criteria:

Loglikelihood user model (H0) -3721.283 -3721.283

Scaling correction factor 1.065

for the MLR correction

Loglikelihood unrestricted model (H1) -3695.092 -3695.092

Scaling correction factor 1.043

for the MLR correction

Akaike (AIC) 7504.566 7504.566

Bayesian (BIC) 7619.487 7619.487

Sample-size adjusted Bayesian (SABIC) 7521.172 7521.172

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation:

RMSEA 0.065 0.064

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.042 0.041

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.089 0.088

P-value H_0: RMSEA <= 0.050 0.133 0.143

P-value H_0: RMSEA >= 0.080 0.158 0.144

Robust RMSEA 0.064

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.040

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.088

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA <= 0.050 0.156

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA >= 0.080 0.147

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual:

SRMR 0.041 0.041

Parameter Estimates:

Standard errors Sandwich

Information bread Observed

Observed information based on Hessian

Latent Variables:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

textual =~

x4 0.989 0.061 16.150 0.000 0.989 0.851

x5 1.103 0.055 20.196 0.000 1.103 0.856

x6 0.916 0.058 15.728 0.000 0.916 0.838

visual =~

x1 0.885 0.091 9.673 0.000 0.885 0.759

x2 0.511 0.082 6.233 0.000 0.511 0.435

x3 0.667 0.072 9.214 0.000 0.667 0.590

x9 0.387 0.066 5.895 0.000 0.387 0.384

speed =~

x7 0.666 0.075 8.874 0.000 0.666 0.612

x8 0.804 0.080 9.997 0.000 0.804 0.795

x9 0.450 0.065 6.901 0.000 0.450 0.447

Covariances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

textual ~~

visual 0.453 0.074 6.091 0.000 0.453 0.453

speed 0.206 0.076 2.731 0.006 0.206 0.206

visual ~~

speed 0.301 0.084 3.567 0.000 0.301 0.301

Intercepts:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

.x4 3.061 0.067 45.694 0.000 3.061 2.634

.x5 4.341 0.074 58.452 0.000 4.341 3.369

.x6 2.186 0.063 34.667 0.000 2.186 1.998

.x1 4.936 0.067 73.473 0.000 4.936 4.235

.x2 6.088 0.068 89.855 0.000 6.088 5.179

.x3 2.250 0.065 34.579 0.000 2.250 1.993

.x9 5.374 0.058 92.546 0.000 5.374 5.334

.x7 4.186 0.063 66.766 0.000 4.186 3.848

.x8 5.527 0.058 94.854 0.000 5.527 5.467

Variances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

.x4 0.373 0.050 7.403 0.000 0.373 0.276

.x5 0.444 0.057 7.827 0.000 0.444 0.267

.x6 0.357 0.046 7.674 0.000 0.357 0.298

.x1 0.576 0.135 4.256 0.000 0.576 0.424

.x2 1.120 0.109 10.296 0.000 1.120 0.811

.x3 0.830 0.087 9.561 0.000 0.830 0.651

.x9 0.558 0.066 8.482 0.000 0.558 0.550

.x7 0.740 0.089 8.266 0.000 0.740 0.625

.x8 0.375 0.105 3.583 0.000 0.375 0.367

textual 1.000 1.000 1.000

visual 1.000 1.000 1.000

speed 1.000 1.000 1.000

R-Square:

Estimate

x4 0.724

x5 0.733

x6 0.702

x1 0.576

x2 0.189

x3 0.349

x9 0.450

x7 0.375

x8 0.633lavaan 0.6-20 ended normally after 39 iterations

Estimator ML

Optimization method NLMINB

Number of model parameters 31

Number of observations 301

Number of missing patterns 1

Model Test User Model:

Standard Scaled

Test Statistic 52.382 51.725

Degrees of freedom 23 23

P-value (Chi-square) 0.000 0.001

Scaling correction factor 1.013

Yuan-Bentler correction (Mplus variant)

Model Test Baseline Model:

Test statistic 918.852 880.082

Degrees of freedom 36 36

P-value 0.000 0.000

Scaling correction factor 1.044

User Model versus Baseline Model:

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.967 0.966

Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 0.948 0.947

Robust Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.968

Robust Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 0.950

Loglikelihood and Information Criteria:

Loglikelihood user model (H0) -3721.283 -3721.283

Scaling correction factor 1.065

for the MLR correction

Loglikelihood unrestricted model (H1) -3695.092 -3695.092

Scaling correction factor 1.043

for the MLR correction

Akaike (AIC) 7504.566 7504.566

Bayesian (BIC) 7619.487 7619.487

Sample-size adjusted Bayesian (SABIC) 7521.172 7521.172

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation:

RMSEA 0.065 0.064

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.042 0.041

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.089 0.088

P-value H_0: RMSEA <= 0.050 0.133 0.143

P-value H_0: RMSEA >= 0.080 0.158 0.144

Robust RMSEA 0.064

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.040

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.088

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA <= 0.050 0.156

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA >= 0.080 0.147

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual:

SRMR 0.041 0.041

Parameter Estimates:

Standard errors Sandwich

Information bread Observed

Observed information based on Hessian

Latent Variables:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

textual =~

x4 0.989 0.061 16.150 0.000 0.989 0.851

x5 1.103 0.055 20.196 0.000 1.103 0.856

x6 0.916 0.058 15.728 0.000 0.916 0.838

visual =~

x1 0.885 0.091 9.673 0.000 0.885 0.759

x2 0.511 0.082 6.233 0.000 0.511 0.435

x3 0.667 0.072 9.214 0.000 0.667 0.590

x9 0.387 0.066 5.895 0.000 0.387 0.384

speed =~

x7 0.666 0.075 8.874 0.000 0.666 0.612

x8 0.804 0.080 9.997 0.000 0.804 0.795

x9 0.450 0.065 6.901 0.000 0.450 0.447

Covariances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

textual ~~

visual 0.453 0.074 6.091 0.000 0.453 0.453

visual ~~

speed 0.301 0.084 3.567 0.000 0.301 0.301

textual ~~

speed 0.206 0.076 2.731 0.006 0.206 0.206

Intercepts:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

visual 0.000 0.000 0.000

textual 0.000 0.000 0.000

speed 0.000 0.000 0.000

.x1 (int1) 4.936 0.067 73.473 0.000 4.936 4.235

.x2 (int2) 6.088 0.068 89.855 0.000 6.088 5.179

.x3 (int3) 2.250 0.065 34.579 0.000 2.250 1.993

.x4 (int4) 3.061 0.067 45.694 0.000 3.061 2.634

.x5 (int5) 4.341 0.074 58.452 0.000 4.341 3.369

.x6 (int6) 2.186 0.063 34.667 0.000 2.186 1.998

.x7 (int7) 4.186 0.063 66.766 0.000 4.186 3.848

.x8 (int8) 5.527 0.058 94.854 0.000 5.527 5.467

.x9 (int9) 5.374 0.058 92.546 0.000 5.374 5.334

Variances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

visual 1.000 1.000 1.000

textual 1.000 1.000 1.000

speed 1.000 1.000 1.000

.x1 0.576 0.135 4.256 0.000 0.576 0.424

.x2 1.120 0.109 10.296 0.000 1.120 0.811

.x3 0.830 0.087 9.561 0.000 0.830 0.651

.x4 0.373 0.050 7.403 0.000 0.373 0.276

.x5 0.444 0.057 7.827 0.000 0.444 0.267

.x6 0.357 0.046 7.674 0.000 0.357 0.298

.x7 0.740 0.089 8.266 0.000 0.740 0.625

.x8 0.375 0.105 3.583 0.000 0.375 0.367

.x9 0.558 0.066 8.482 0.000 0.558 0.550

R-Square:

Estimate

x1 0.576

x2 0.189

x3 0.349

x4 0.724

x5 0.733

x6 0.702

x7 0.375

x8 0.633

x9 0.4507.10.10.4 Estimates of Model Fit

After fitting the additional factor loading, the model fits well according to RMSEA, CFI, and SRMR, and the model fit is acceptable according to TLI. Thus, this model could be defensible.

Code

chisq df pvalue

52.382 23.000 0.000

chisq.scaled df.scaled pvalue.scaled

51.725 23.000 0.001

chisq.scaling.factor baseline.chisq baseline.df

1.013 918.852 36.000

baseline.pvalue rmsea cfi

0.000 0.065 0.967

tli srmr rmsea.robust

0.948 0.041 0.064

cfi.robust tli.robust

0.968 0.950 7.10.10.5 Residuals

$type

[1] "cor.bollen"

$cov

x4 x5 x6 x1 x2 x3 x9 x7 x8

x4 0.000

x5 0.005 0.000

x6 -0.008 0.003 0.000

x1 0.080 -0.001 0.069 0.000

x2 -0.015 -0.029 0.028 -0.033 0.000

x3 -0.069 -0.152 -0.026 -0.008 0.083 0.000

x9 -0.018 0.000 -0.009 -0.003 -0.019 0.023 0.000

x7 0.066 -0.006 0.015 -0.073 -0.156 -0.037 -0.003 0.000

x8 -0.033 -0.002 0.012 0.042 -0.012 0.045 0.002 0.000 0.000

$mean

x4 x5 x6 x1 x2 x3 x9 x7 x8

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 7.10.10.6 Path Diagram

Below is a path diagram of the model generated using the semPlot package (Epskamp, 2022).

Figure 7.10: Modified Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model.

7.10.10.7 Compare Model Fit

The modified model with the cross-loading and the original model are considered “nested” models.

The original model is nested within the modified model because the modified model includes all of the terms of the original model along with additional terms.

To confirm that the models are nested, I use the net() function from the semTools package (Jorgensen et al., 2021).

If cell [R, C] is TRUE, the model in row R is nested within column C.

If the models also have the same degrees of freedom, they are equivalent.

NA indicates the model in column C did not converge when fit to the

implied means and covariance matrix from the model in row R.

The hidden diagonal is TRUE because any model is equivalent to itself.

The upper triangle is hidden because for models with the same degrees

of freedom, cell [C, R] == cell [R, C]. For all models with different

degrees of freedom, the upper diagonal is all FALSE because models with

fewer degrees of freedom (i.e., more parameters) cannot be nested

within models with more degrees of freedom (i.e., fewer parameters).

cfaModel2Fit cfaModelFit

cfaModel2Fit (df = 23)

cfaModelFit (df = 24) TRUE Model fit of nested models can be compared with a chi-square difference test.

In this case, the model with the cross-loading fits significantly better (i.e., has a significantly smaller chi-square value) than the model without the cross-loading.

One can also compare nested models using a robust likelihood ratio test:

Code

Model 1

Class: lavaan

Call: lavaan::lavaan(model = cfaModel2_syntax, data = HolzingerSwineford1939, ...

Model 2

Class: lavaan

Call: lavaan::lavaan(model = cfaModel_syntax, data = HolzingerSwineford1939, ...

Variance test

H0: Model 1 and Model 2 are indistinguishable

H1: Model 1 and Model 2 are distinguishable

w2 = 0.120, p = 0.00049

Robust likelihood ratio test of distinguishable models

H0: Model 2 fits as well as Model 1

H1: Model 1 fits better than Model 2

LR = 32.923, p = 8.11e-08For non-nested models, one can compare model fit with AIC, BIC, or the Vuong test.

aic bic bic2

7535.490 7646.703 7551.560 aic bic bic2

7504.566 7619.487 7521.172

Model 1

Class: lavaan

Call: lavaan::lavaan(model = cfaModel_syntax, data = HolzingerSwineford1939, ...

Model 2

Class: lavaan

Call: lavaan::lavaan(model = cfaModel2_syntax, data = HolzingerSwineford1939, ...

Variance test

H0: Model 1 and Model 2 are indistinguishable

H1: Model 1 and Model 2 are distinguishable

w2 = 0.120, p = 0.00049

Non-nested likelihood ratio test

H0: Model fits are equal for the focal population

H1A: Model 1 fits better than Model 2

z = -2.734, p = 0.997

H1B: Model 2 fits better than Model 1

z = -2.734, p = 0.0031287.11 Structural Equation Model (SEM)

The structural equation models were fit in the lavaan package (Rosseel et al., 2022).

The examples were adapted from the lavaan documentation: https://lavaan.ugent.be/tutorial/sem.html (archived at https://perma.cc/8NG9-7JAG).

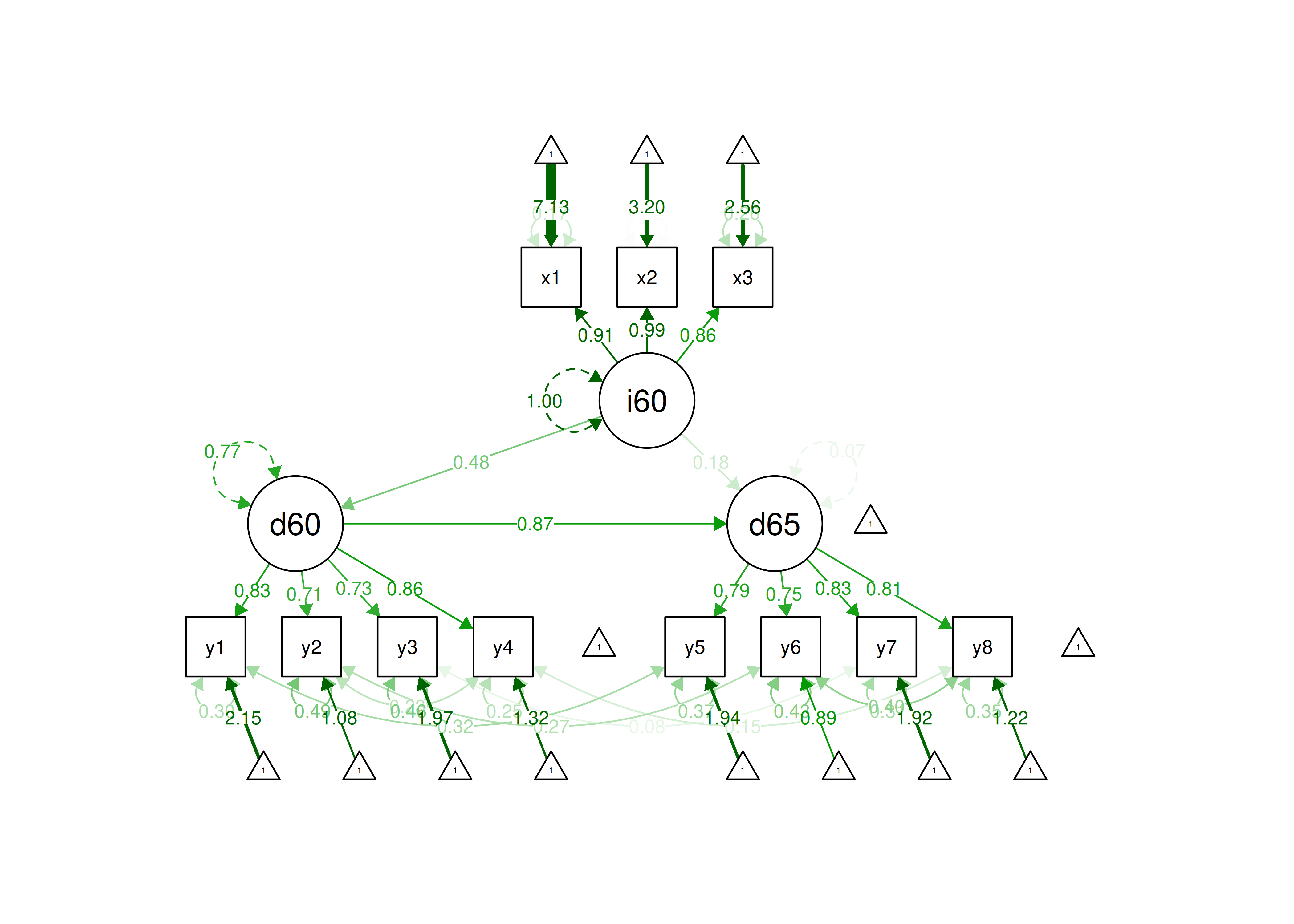

In this model, we fit a measurement model with three latent factors in addition to a structural model with regressions estimated among the latent factors.

7.11.1 Specify the Model

Code

semModel_syntax <- '

#Measurement model factor loadings

ind60 =~ x1 + x2 + x3

dem60 =~ y1 + y2 + y3 + y4

dem65 =~ y5 + y6 + y7 + y8

#Regression paths

dem60 ~ ind60

dem65 ~ ind60 + dem60

#Covariances among residual variances (correlated errors)

y1 ~~ y5

y2 ~~ y4 + y6

y3 ~~ y7

y4 ~~ y8

y6 ~~ y8

'

semModel_fullSyntax <- '

#Measurement model factor loadings (free the factor loading of the first indicator)

ind60 =~ NA*x1 + x2 + x3

dem60 =~ NA*y1 + y2 + y3 + y4

dem65 =~ NA*y5 + y6 + y7 + y8

#Regression paths

dem60 ~ ind60

dem65 ~ ind60 + dem60

#Covariances among residual variances (correlated errors)

y1 ~~ y5

y2 ~~ y4 + y6

y3 ~~ y7

y4 ~~ y8

y6 ~~ y8

#Fix latent means to zero

ind60 ~ 0

dem60 ~ 0

dem65 ~ 0

#Fix latent variances to one

ind60 ~~ 1*ind60

dem60 ~~ 1*dem60

dem65 ~~ 1*dem65

#Estimate covariances among latent variables (not necessary because the latent variables are already linked via regression paths)

#Estimate residual variances of manifest variables

x1 ~~ x1

x2 ~~ x2

x3 ~~ x3

y1 ~~ y1

y2 ~~ y2

y3 ~~ y3

y4 ~~ y4

y5 ~~ y5

y6 ~~ y6

y7 ~~ y7

y8 ~~ y8

#Free intercepts of manifest variables

x1 ~ intx1*1

x2 ~ intx2*1

x3 ~ intx3*1

y1 ~ inty1*1

y2 ~ inty2*1

y3 ~ inty3*1

y4 ~ inty4*1

y5 ~ inty5*1

y6 ~ inty6*1

y7 ~ inty7*1

y8 ~ inty8*1

'7.11.3 Display Summary Output

7.11.3.1 Interpreting lavaan Output

Output from a SEM model includes information such as regression coefficients, intercepts, variances, and model fit indices.

As noted above, there are two chi-square tests.

In lavaan syntax, one is labeled “Model Test User Model” and the other is labeled “Model Test Baseline Model.”

The chi-square test labeled “Model Test User Model” refers to the chi-square test of whether the model fits worse than the best-possible fitting model (the saturated model).

In this case, the p-value of the robust chi-square test is \(0.17\).

Thus, the model does not show significant misfit—i.e., the model does not fit significantly worse than the best-possible fitting model.

The chi-square test labeled “Model Test Baseline Model” refers to the chi-square test of whether the model fits better than the worst-possible fitting model (the null model).

In this case, the p-value of the robust chi-square test in comparison to the worse-possible fitting model is < .05.

Thus, the model fits significantly better than the worst-possible-fitting model.

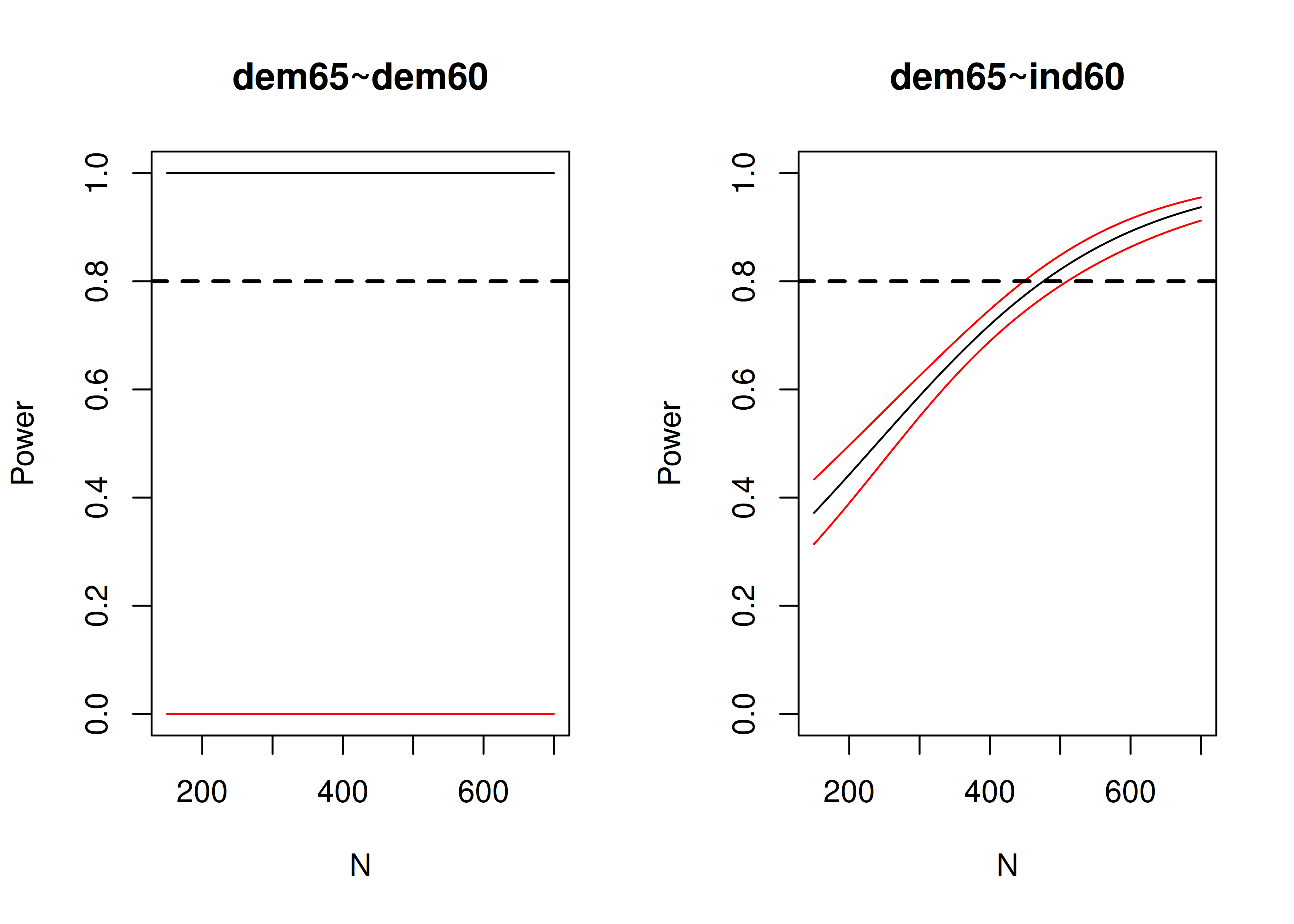

In terms of the model findings, ind60 was significantly positively associated with dem60, dem60 was significantly positively associated with dem65, and ind60 was marginally significantly positively associated with dem65.

lavaan 0.6-20 ended normally after 82 iterations

Estimator ML

Optimization method NLMINB

Number of model parameters 42

Number of observations 75

Number of missing patterns 36

Model Test User Model:

Standard Scaled

Test Statistic 38.748 42.709

Degrees of freedom 35 35

P-value (Chi-square) 0.304 0.174

Scaling correction factor 0.907

Yuan-Bentler correction (Mplus variant)

Model Test Baseline Model:

Test statistic 601.314 594.441

Degrees of freedom 55 55

P-value 0.000 0.000

Scaling correction factor 1.012

User Model versus Baseline Model:

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.993 0.986

Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 0.989 0.978

Robust Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.988

Robust Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 0.981

Loglikelihood and Information Criteria:

Loglikelihood user model (H0) -1418.424 -1418.424

Scaling correction factor 0.989

for the MLR correction

Loglikelihood unrestricted model (H1) -1399.050 -1399.050

Scaling correction factor 0.952

for the MLR correction

Akaike (AIC) 2920.848 2920.848

Bayesian (BIC) 3018.183 3018.183

Sample-size adjusted Bayesian (SABIC) 2885.810 2885.810

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation:

RMSEA 0.038 0.054

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.000 0.000

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.094 0.106

P-value H_0: RMSEA <= 0.050 0.585 0.424

P-value H_0: RMSEA >= 0.080 0.126 0.240

Robust RMSEA 0.055

90 Percent confidence interval - lower 0.000

90 Percent confidence interval - upper 0.113

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA <= 0.050 0.422

P-value H_0: Robust RMSEA >= 0.080 0.279

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual:

SRMR 0.046 0.046

Parameter Estimates:

Standard errors Sandwich

Information bread Observed

Observed information based on Hessian

Latent Variables:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

ind60 =~

x1 0.645 0.056 11.566 0.000 0.645 0.908

x2 1.495 0.124 12.084 0.000 1.495 0.991

x3 1.189 0.112 10.581 0.000 1.189 0.863

dem60 =~

y1 1.879 0.239 7.858 0.000 2.143 0.834

y2 2.477 0.308 8.043 0.000 2.825 0.714

y3 2.134 0.330 6.469 0.000 2.434 0.733

y4 2.523 0.254 9.918 0.000 2.879 0.864

dem65 =~

y5 0.547 0.228 2.398 0.016 2.090 0.791

y6 0.656 0.275 2.390 0.017 2.509 0.753

y7 0.715 0.315 2.265 0.024 2.732 0.830

y8 0.696 0.311 2.240 0.025 2.660 0.805

Regressions:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

dem60 ~

ind60 0.549 0.162 3.381 0.001 0.481 0.481

dem65 ~

ind60 0.690 0.391 1.766 0.077 0.180 0.180

dem60 2.900 1.362 2.129 0.033 0.865 0.865

Covariances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

.y1 ~~

.y5 0.728 0.511 1.427 0.154 0.728 0.318

.y2 ~~

.y4 1.087 0.847 1.284 0.199 1.087 0.234

.y6 1.672 0.957 1.747 0.081 1.672 0.275

.y3 ~~

.y7 0.343 0.750 0.457 0.647 0.343 0.083

.y4 ~~

.y8 0.501 0.457 1.097 0.273 0.501 0.153

.y6 ~~

.y8 1.720 0.843 2.040 0.041 1.720 0.400

Intercepts:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

.x1 5.064 0.084 60.554 0.000 5.064 7.131

.x2 4.829 0.176 27.401 0.000 4.829 3.202

.x3 3.524 0.163 21.557 0.000 3.524 2.557

.y1 5.512 0.300 18.389 0.000 5.512 2.145

.y2 4.273 0.468 9.127 0.000 4.273 1.080

.y3 6.558 0.385 17.026 0.000 6.558 1.974

.y4 4.391 0.392 11.214 0.000 4.391 1.319

.y5 5.132 0.312 16.434 0.000 5.132 1.942

.y6 2.979 0.390 7.642 0.000 2.979 0.894

.y7 6.310 0.387 16.315 0.000 6.310 1.918

.y8 4.019 0.392 10.247 0.000 4.019 1.217

Variances:

Estimate Std.Err z-value P(>|z|) Std.lv Std.all

.x1 0.088 0.023 3.792 0.000 0.088 0.175

.x2 0.040 0.097 0.410 0.682 0.040 0.017

.x3 0.486 0.090 5.418 0.000 0.486 0.256

.y1 2.009 0.506 3.973 0.000 2.009 0.304

.y2 7.675 1.433 5.354 0.000 7.675 0.490

.y3 5.116 1.157 4.420 0.000 5.116 0.463

.y4 2.803 0.883 3.175 0.001 2.803 0.253

.y5 2.618 0.686 3.815 0.000 2.618 0.375

.y6 4.819 0.987 4.884 0.000 4.819 0.434

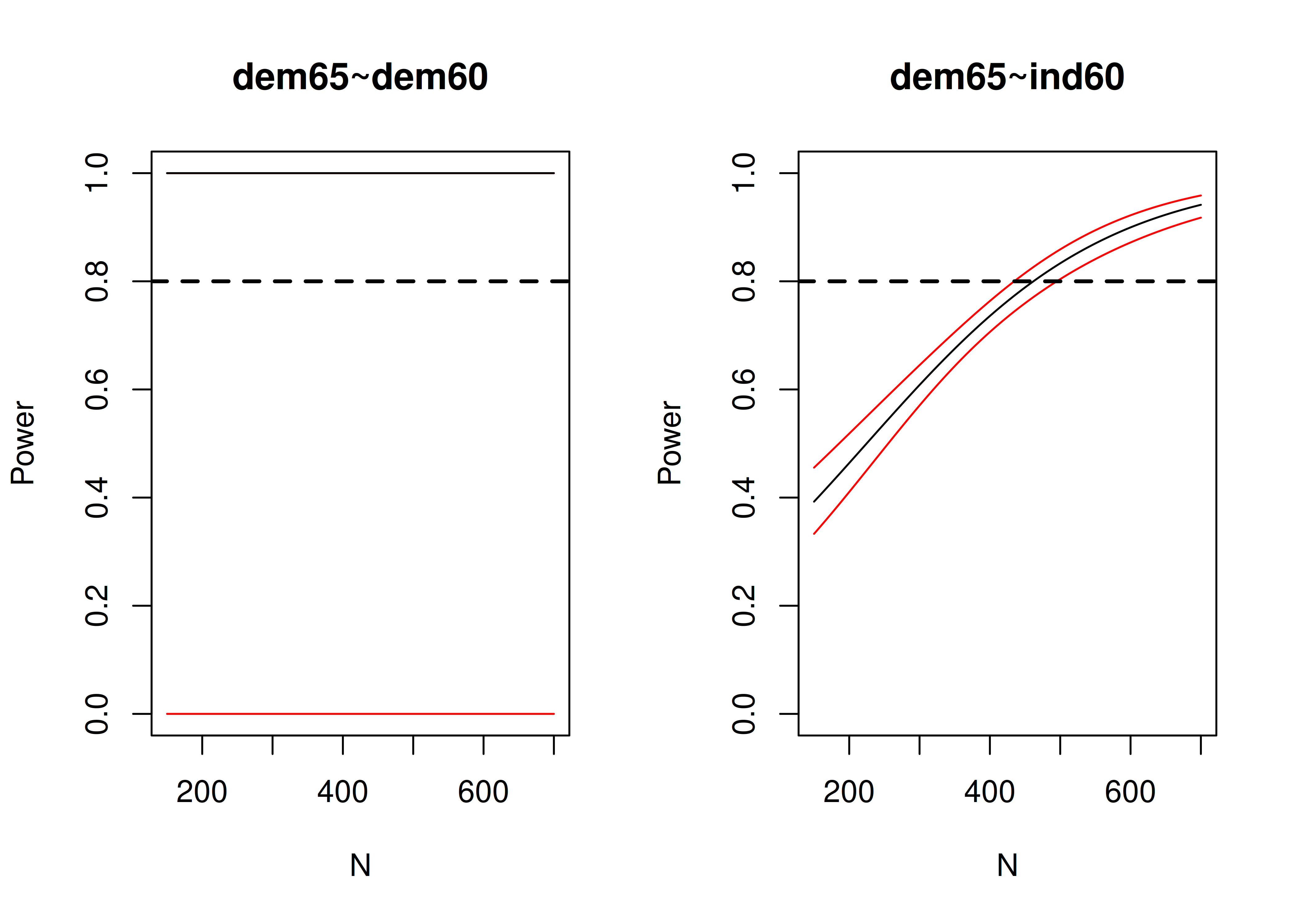

.y7 3.362 0.714 4.709 0.000 3.362 0.311